In 1996, Muhanned Cader, then a recent graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, rented a studio overlooking Bolgoda Lake, a picturesque reservoir outside the Sri Lankan capital, Colombo. Bolgoda was a prepossessing location to the young Cader, who was attracted to the quixotic local landscape. Here, Cader created a series of 40 paintings, "Nightscapes" (1999), which depict the view across the lake from the artist's studio. The paintings show strands of light, cast from a row of houses across the lake, reflected back across the still water. Little else stirs. Instead, a suggestion of what cannot be seen or witnessed lingers in the darkness. In hindsight, the paintings appear to capture the terror prevalent in Sri Lanka during the 1990s when victims of extra-judicial killings were reportedly found floating on the lake.

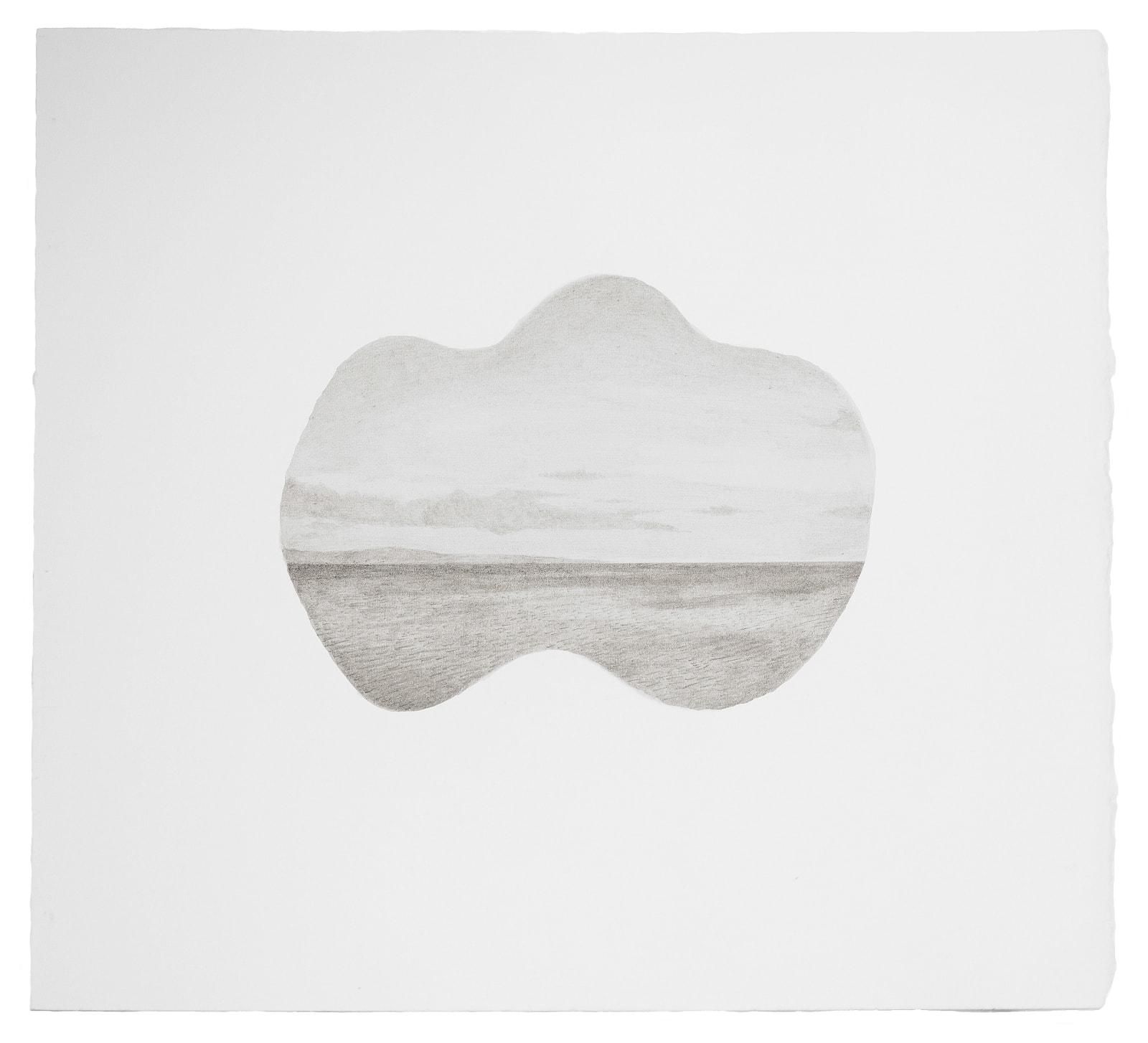

In their curved, cloud-like shape, each panel in the series points to the influence of Hawaiian-born artist Ray Yoshida. A teacher at the Art Institute of Chicago since 1959, Yoshida, along with Jim Nutt and Roger Brown, formed the irreverent figurative painting movement known as the Chicago Imagists during the 1960s. In his own work, Yoshida carefully cuts irregular, jagged shapes from comic strips and arranges them into neat rows that form larger grids. In such works as Pool (1999) or Aughh! (2000), Yoshida assembles familiar details of hair, clothing and buildings that appear to allude to one another or some totality but are ultimately no more than a grouping of missing parts or fragments. In these collages, Yoshida deftly exploits the ambiguity of carefully chosen details to suggest absurd or surreal readings. And yet the image, though mesmerizing, remains incomplete and cannot be read as the sum of its many parts.

The relationship between parts and the whole is a central concern to Cader and attests to his assimilation of Yoshida's teachings. The blob-like shapes in 79 Days in Lahore (2002), Cader's collection of79 small-scale drawings made while on a residency in Pakistan, variously resemble undersea creatures or internal organs, which, in their strangeness, evoke the mysteries uncovered in an unfamiliar city. In "The One Year Drawing Project" (2005-07), a 29-month-long drawing exchange-the project grew in length in part because of the unreliability of the Sri Lankan postal service-involving three other Sri Lanka artists, Cader started with an evocative but amorphous stenciled form. Over the course of the project, he mischievously mutated this suggestive shape into a.ii everimaginative series of surreal anthropomorphic objects, which are alternately peaceful and disturbing. Beyond the Yoshidalike obsession with uncanny forms, Cader pushes his teacher's irreverent sense of humor back into the realm of the imaginary which, paradoxically, evokes real-world events.

-Sharmini Pereira