With extreme discipline, Nasreen Mohamedi’s drawn lines seek to chart the rhythms of wind across desert sands, ocean tides, the play of shadows on outdoor stairways, or across the facades of the Islamic architecture she so admired. “Detached Joy,” she wrote at the top of one of the pages of one of her many diaries. Indeed, joy and detachment conflate and fill her drawings from the 1970s, a selection of which was recently on view at the Talwar Gallery in New York.

Born into a prosperous Muslim family, in 1937, in Karachi (then still part of India), Mohamedi was raised in Bombay (now Mumbai) and later attended St. Martin’s School in London from 1954 to 1957 and lived in Paris from 1961 to 1963. She returned to India well-schooled in European modernism and joined the Bhulabhai Institute for the Arts, where she eschewed the narrative painting prevalent at the time; her loosely painted figuration was at a far remove from the tightly rendered Hindu gods and goddesses painted by M.F. Husain (b. 1915), most recently reviled for painting “Mother India” in the nude, as well as the surrealist-influenced figuration of Tyeb Mehta (b. 1925), both of whom were at Bhulabhai with her. Instead, she was drawn to and mentored by V.S. Gaitonde (1924-2001) whose close-toned, meticulous Miró-and-Klee influenced paintings made him on of India’s rare but highly regarded abstractionists. She initiated a dialogue with the younger Jeram Patel (b. 1930), an abstractionist given to aqueous biomorphic configuration.

Slowly Mohamedi moved toward abstraction; her art became as international as her education and wide travel (she visited Iran, Japan, the United States, and her native India). Kazimir Malevich was an influence as was the Islamic architecture she sought out in Turkey, Iran and Rajasthan. Though raised as a Muslim, she found inspiration in Zen Buddhism. She was readily attracted to the vastness of the desert; as a still photographer, she accompanied Husain to the deserts of Rajasthan as he worked on an autobiographical film. However, she was also drawn to airplane runways, cars, and modern urban architecture. She would seek an art revelatory of the underlying patterns and forces of nature as well as those of human endeavor.

Mohamedi’s diaries from the late 1960s prefigured her mature drawings, recording the travel and weight of

the lines, the light of lines interspersed with written thoughts on line’s possibilities, her hopes for lines,

occasionally her solitude, often her wonder. Dense accumulations of line on each page are only occasionally

interrupted by written words. On July 4, 1967, she wrote:

Where do I stand in relation to space and thought

The layers in Indian sculpture, in Arabic calligraphy

In waves—in connection with my work

No question mark accompanied this deep question; the answer was already forming. While Malevich’s spare geometries influenced her, Mohamedi was not in search of his idealized purities nor did she wish to emulate the coolly depersonalized simple geometries of such artists as Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd.

With the straight and/or diagonal lines that became her sole vocabulary in the 1970s, Mohamedi distilled her experiences of those elements in the natural and man-made phenomena to which she was most strongly attracted. The Zen Buddhism she embraced fostered an emphasis on wisdom based on experience and achieved through meditation. Her lines seek to materialize. With her totally abstract means, she evoked not only rectilinear phenomena such as a skyscraper or mosque courtyard but also those natural phenomena normally only charted with curvilinearities, such as the wind’s movement across water or desert sands. Close inspection of Mohamedi’s drawn lines reveals the painstaking, time-consuming process of their making—tremors of intent slowly congregate in previously unseen calligraphy created solely with straight lines—perhaps heeding the ancient Muslim ban on figurative representation while, like Arabic calligraphy, resonating with the subject signified by its accumulation of written marks. Mohamedi navigated the paper planes with rulers, set squares, pencils, brushes, pens, ink, and a specially designed compass. She diluted her ink to different tonalities and applied the ink to the pen with a brush. She also alternated ink and graphite lines. Several weeks might readily be consumed by a single drawing as it became a meditation upon its making. “One creates dimensions out of solitude,” states a diary entry from the “3rd of September, 1967.”

The origins of Mohamedi’s abstractions can often be found in the photographs she took of the desert, the Fatehpur Sikri palace complex, reflective skyscraper facades, a stone stairway, and a loom strung with vertical threads that look remarkably like one of her drawings. She never sought to exhibit these photographs. But one or another seems to have functioned as a kind of preparatory sketch or study, the tilted angle of the camera lens and close cropping into near abstraction typical of many of them are frequently translated into the drawings’ language of lines, especially those where an accumulation of diagonals move into and out of the paper plane as though rendered in perspective.

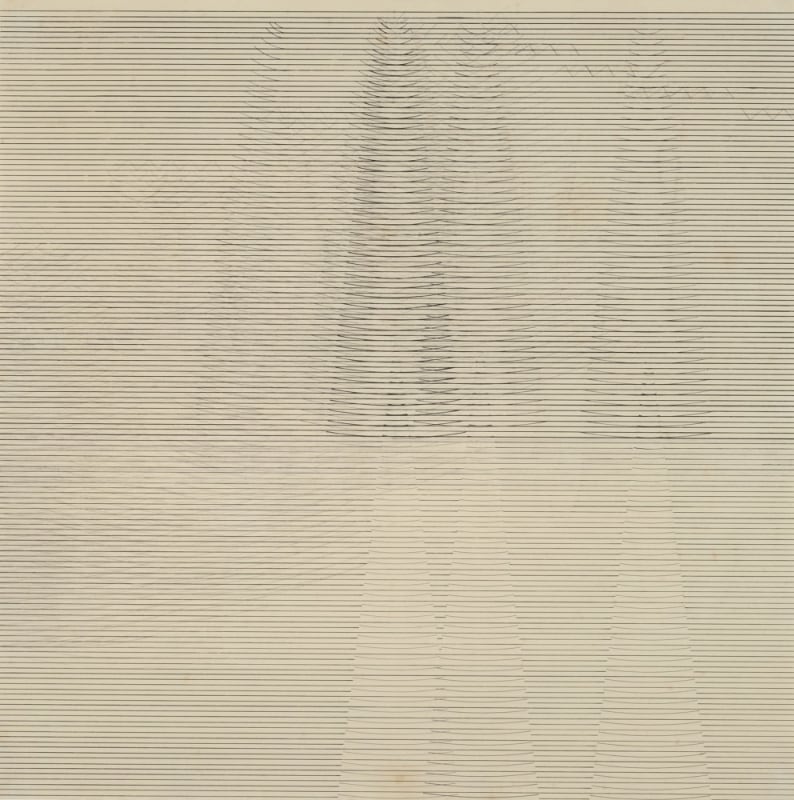

Mohamedi has frequently been compared to Agnes Martin; indeed, the two were paired in Documenta 12 in 2007. While both artists depended upon a firm and rigorous-yet-gentle linearity, Martin’s horizontal lines, occasionally joined by verticals to form a grid, hover in congruence with the square plane of her support, whereas Mohamedi’s horizontal and diagonal lines warp the plan with what appears to be vast networks of tremors and vibrations that pass through the 18 3/4 x 18 3/4 inch or 7 1/2 x 7 1/2 inch paper planes. They often barely cross the threshold of perception. In one of her drawings created in the 1970s, two registers of horizontal lines enter from right and left; in the upper half, through the most delicate and precise increases in pressure on the pencil, a cone of spiraling linearity emerges together with two almost invisible reflections to the right and one to the left. The subtlest shifts in pressure turn horizontal lines into “hypnotic contrasting rhythms” to quote another diary entry. Almost empty, full of movement, no closure—one might spend a day or two trying to follow the path of each line before surrendering it to infinity or give oneself up to meditating upon this rhythmic emptiness. In another drawing, vertical and horizontal linearity meet in what might be a shimmering rendition of glass-clad skyscrapers so delicate that spiders could have spun them.

In the 1980s, arcs, ovals, circles, and triangles began to float in stillness on Mohamedi’s planes. I have seen but one of these drawings and so can hold no qualified opinion of them. However, the drawings she created in the 1970s more than entitle her to the posthumous critical acclaim they have garnered. Her hand, so finely tuned to nuance and precision, would be increasingly obstructed by the Parkinson’s disease she died of in 1990.

-Klaus Kortoss