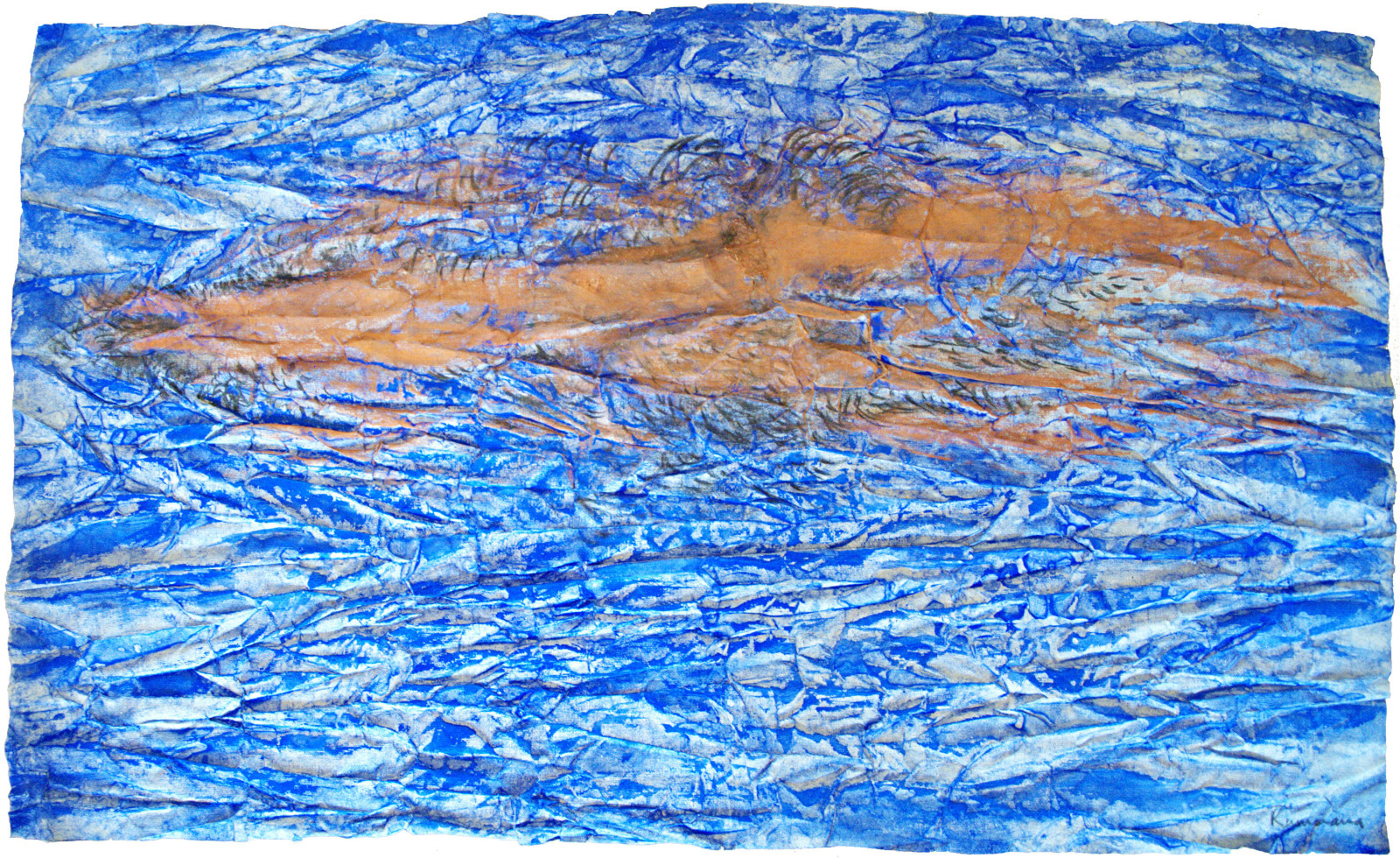

Crushed blue piece, 1992

Indigo, earth pigment and charcoal on crushed paper

19″ x 29 3/4″

In 1995, Rummana Hussain walked through the precincts of the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Mumbai, her mouth wide open in a soundless scream. In a performance titled Living on the Margins, her first ever, she cushioned a halved papaya in her hands, revealing black seeds nestling against its creamy orange flesh. The hollow of the tropical fruit appeared to echo her gaping mouth while simultaneously evoking female genitalia. For bystanders who might, in retrospect, have wondered about the origins of this fruity symbolism, Hussain’s recent show “Breaking Skin” was strewn with plenty of clues. It brought together a body of work executed between 1992 and 1994, just preceding her powerful performance in Mumbai. Clearly the ideas for her feminist imagery were incubating during this period, as evident in her paintings Fatal Echo (Labia Majora) and Fatal Echo (Latent Seed), both 1993, in which halved papayas occupy center stage. Hussain’s exploration of the narrative of the fertile female body and the more feminist concerns inscribed in it are also evident in Yoni and Bodyscape, both 1993, and in the “Tunnel Echoes” series, 1994, focusing on the iconography of the vagina.

Eschewing more conventional materials favored by Indian artists at the time, Hussain turned instead to earth pigments, indigo, terra-cotta, iron nails, and charcoal. She often used photocopies, either juxtaposed against painted images, as in Dissemination, 1993, or in One into three, 1993, in which partially distorted images from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment can also be deciphered. In her abstract creations Crushed blue piece, 1992, and Love over reason, 1993, she experimented with different textures of paper, crumpling or folding it to create gridlike forms.

But the early ’90s was also a time when Hussain was suddenly made conscious of her identity as part of a minority Muslim community in a predominantly Hindu country. This awareness was triggered by the wanton destruction of a sixteenth-century mosque, the Babri Masjid, in 1992 by right-wing Hindu militants. In the aftermath, communal riots occurred in several parts of the country; Mumbai, the city where Hussain lived, was particularly affected. Over the years Hussain would also use her body as a site to enact the turmoil in the larger body politic, advocating the need for more secular values.

Her struggle to find a vocabulary to express this rediscovered facet of her identity was clearly visible in the show. Photocopies of a newspaper photograph depicting triumphant hooligans atop the domes of the mosque find their way into the two-part mixed-media work Behind a thin film, 1993. As she did with the papaya, here Hussain was also exploring analogies between the semicircular form of the dome and parts of the female anatomy, correspondences that she would harness in subsequent works. Hussain’s play on the metaphor of body as vessel is evident in the terra-cotta pot she uses in Tower of Babel and Earth picture, both 1993. In the latter, the connotations of the pot are expanded, serving as a symbol for the larger universe, though rupture is inscribed in the shattered shards strewn across both works. “Breaking Skin” served as a testimony to how Hussain, who succumbed to breast cancer at the age of forty-seven in 1999, succeeded in forging an imagery that was deeply personal and yet capable of articulating more universal concerns.

-Meera Menezes