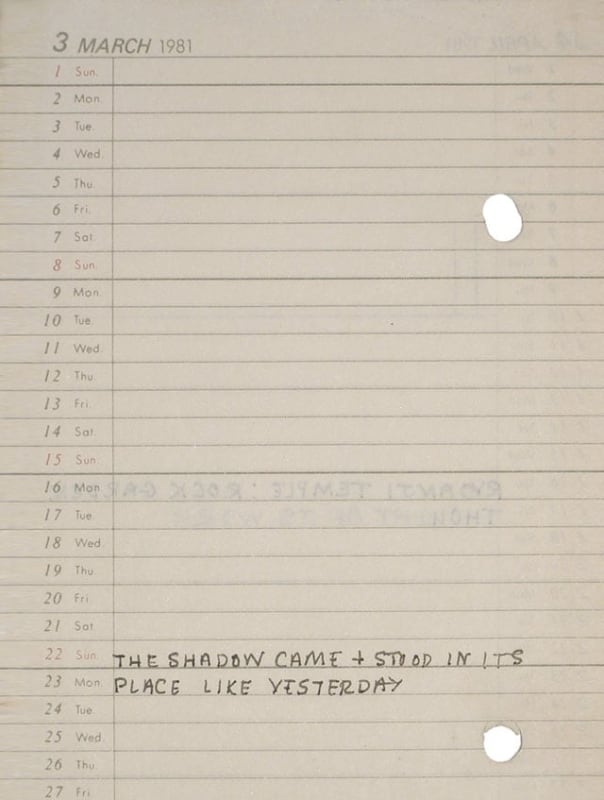

Diary Page

India’s Nasreen Mohamedi Belongs to Everyone

After the filmmaker Nagisa Oshima was called the “Japanese Godard” for what must have been the umpteenth time, he wittily replied by calling Godard “the French Oshima.”

I thought of Oshima’s response once more when I went to Nasreen Mohamedi: Becoming One at the Talwar Gallery (September 13–November 23). I first wrote about Mohamedi’s meticulous line drawings and abstract photographs in the Brooklyn Rail (December 2008–January 2009) and now, five years later, I found that the work has grown more powerful over time. It is like reading a poem that you have read before and thought you had gotten all it could offer, and instantly realizing that there was much more there, perhaps an inexhaustible amount.

Mohamedi is one of the great modern artists of the Indian subcontinent. In addition to drawing, taking photographs and making photograms (only the drawings were exhibited in her lifetime), she kept a small, pocket-sized diary – pages of which are included in the current exhibition.” If the diaries are any indication, Mohamedi thought about art and meaning throughout nearly all her waking hours.

She was born in Karachi (which was once part of India but is now part of Pakistan) in 1937 and died of a hereditary neurological disease in the relatively isolated coastal town of Kihim, about one hundred miles from Mumbai, in 1990. Despite the gradual deterioration of her motor functions, she was able to maintain the scrupulousness of her line until her death at age 53.

As a teenager, Mohamedi went to England, studying at St. Martin’s School, London, from 1954 to 1957, and privately in Paris from 1961 until 1963. She traveled extensively throughout her life, and was influenced by Islamic architecture and Zen aesthetics, which she encountered in Turkey, Iran, Kuwait and Japan. From 1972 until 1988, she taught at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. During this time she became friends with the reclusive V. S. Gaitonde (1924–2001), the pioneer of non-objective painting in India. While the full history of abstraction in India is little known outside of that country, Mohamedi’s secure place in her nation’s pantheon is apparent. It is out of modern Indian art that Mohamedi’s evolved, and it is a disservice to her to compare her work to that of Western artists such as Agnes Martin. She is no more the Martin of India than Martin is the Mohamedi of America. Being satisfied with noticing similarities is the lazy way of writing about art.

In her black-and-white photographs, Mohamedi will sometimes resort to high contrast to isolate a form — a black arch, for example — against a bright white ground. In other, slightly grainier photographs, she focuses on undulating furrows (at least that is what they seem to be) that evoke an earth that is moving, like the sea. And in still other photographs, she directs the viewer’s attention toward slanted white lines indicating parking spaces repeated on the street. Towards the end of her life, she photographed some of her drawings on paper, which appears to be stained with a brown wash, expanding the way they can be read to include a tilled landscape. Running the gamut from light to dark and evoking texture from the immaterial to the material, Mohamedi’s stark, abstract photographs and photograms — which for this artist were a form of drawing — isolate dynamic forms and geometric configurations, a line or lines moving through space.

This sense of movement, repetition and interval is found everywhere in her drawings, which she did on brown paper, graph paper and cream-colored paper. The lines are firm, precise and delicate; their identity is the partly the result of how much pressure Mohamedi applied to the pencil. The faintness and delicacy of some of the lines — they seem to be fading before our eyes — give structure to the ephemeral: the geometric wisps that seem to vanish as they move steadily across the paper. She is determined to locate where is — a body moving through space — as well as go straight into infinity with her eyes open.

In the pencil drawings done on graph paper, she seems to describing a curved object of some kind, a vessel or body that is not solid, but open to the world. The lines extending beyond the austerely sensual contours of the form convey a body in movement through time and space. There is a serene nakedness — a quiet, profound sense of calm — to Mohamedi’s drawings, as she patiently structures time and space into clusters, intervals and curves. They are resolute and vulnerable. They never become an image and even at their most repetitive they do not become a pattern. Rather, they are trajectories. But more to the point, they are really not like anything else.

-John Yau