A wound is a fissure. An otherwise silent surface rends, exposing its viscera. The subsequent experience of agony is primal. Though every wound is personal, there is only one possible cure: to write into the abrasion, for a wound can also be a space for healing. Writing into the open lesion demands a certain irrepressibility.

But, perhaps, to be truly irrepressible one must move beyond the matrix of language. If the performer is a woman, the syntax must be doubly revitalized so that her speech can audibly enter the domain of the public. “The sheer fact of women talking, being, paradoxical, inexplicable, flip, self-destructive, but above all else public is the most revolutionary thing in the world,” American writer and film-maker Chris Kraus once wrote in her genre-defying book I Love Dick, published in 1997. Two years later, Rummana Hussain, an Indian artist who not only exemplified the irrepressible impulse to harness the wound but was also one of the pioneers in the performance and articulation of its mystical facility, lost the battle against breast cancer. She had just turned 47.

In 1995, armed with a halved papaya fruit, her gaping mouth producing soundless screams, Hussain made her formal entry into the world of performance, even inaugurating its conception as an artistic genre within the landscape of contemporary Indian art. Titled Living On The Margins, her performance piece in the open courtyard of the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, was perhaps the consequence of her long engagement with the subject of the female body and its relationship with identity.

Her art and its themes were affected by the deep trauma of being Muslim in a country that was reeling from the communal atmosphere provoked by the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992. Before Ayodhya, Hussain’s Islamist roots were more of a cultural influence than a religious one. Her Muslim identity became a source of much introspection in later performances, most notably in her 1997 work The Tomb Of Begum Hazrat Mahal,

an installation piece that incorporated her preferred motif, the half papaya, and referenced the role played by the Mughal queen as a rebellious figure against the British East India Company during the revolt of 1857.

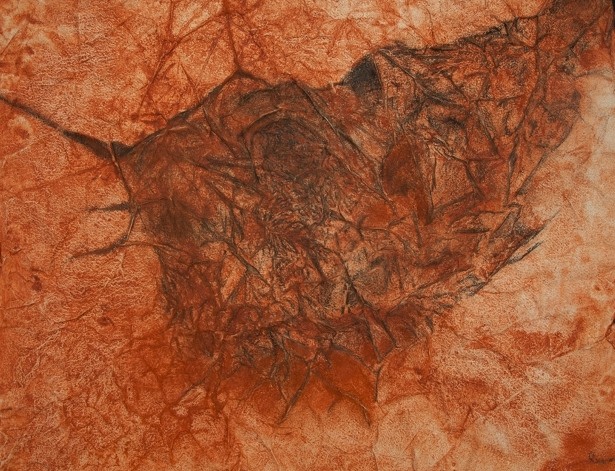

Breaking Skin, an ongoing show at New Delhi’s Talwar Gallery, offers us a glimpse of the breakthroughs and the evolutionary make-up that led Hussain to arrive at such a historically momentous work. Composed of 18 works, all created in the early 1990s, the exhibition allows visitors a glimpse of her process of transition, from flat-painted, two-dimensional planes to textured and ravaged surfaces in diverse media, from a veiled exploration of self to a public, vulnerable personal awakening. It reflects on that moment in time when she rejected the materials that were otherwise used to create high art in lieu of more local and organic material, such as indigo, earth pigment, charcoal and terracotta.

Spread across two floors, Breaking Skin reveals Hussain’s obsession with writing into wounds. She recreated ruptured surfaces on paper and then stained them with indigo or gheru to punctuate the borders of the lacerations. Her use of the photocopied image was inventive, as was her employment of shards of terracotta, intended to represent an archaeological framework of the broken nature of something that was once intact, that could only be made whole by suturing the fragments. The repeated use of the hemispherical dome was her way of directly engaging with the architectural influences that shaped the Babri Masjid.

The show is evidence of Hussain’s inability to stay quiet in the face of communal rioting as well as the violence inflicted upon women as collateral damage. Her activist spirit haunts each piece, as well as her persistence in universalizing the personal struggle.

“It is necessary to emerge from our insular shells to come together and try and develop symbols of secularism... a coming together of artists and viewers is a form of public participation, one that emphasizes the commonality of all,” she once said, echoing the superbly complex question Kraus once asked: “If women have failed to make ‘universal’ art because we’re trapped within the ‘personal’, why not universalize the ‘personal’ and make it the subject of our art?”

-Rosalyn D'Mello