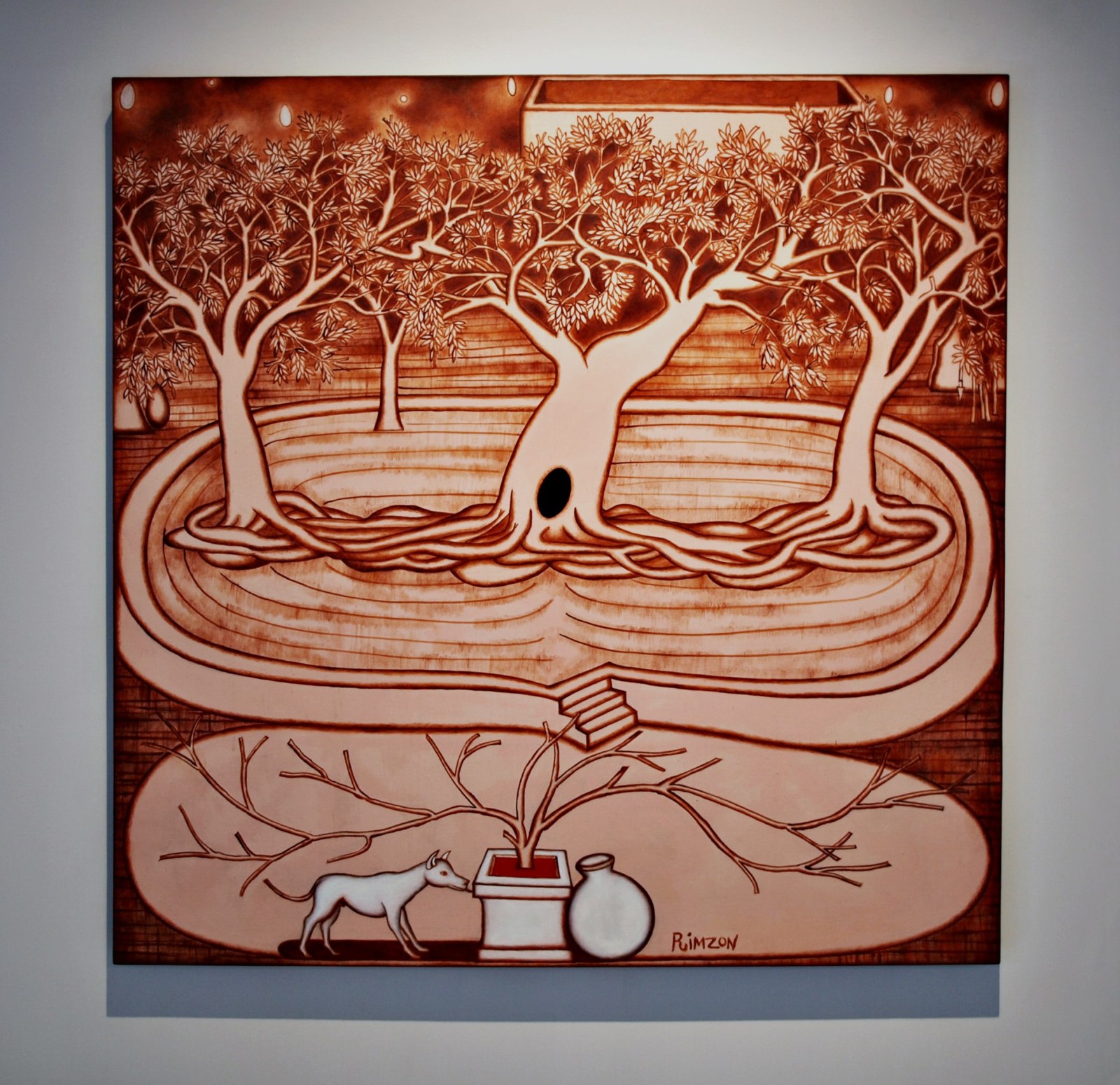

Tree Shrine, 2012

Acrylic on canvas

40″ x 39 3/4″

The Modernist Sprawl

Like many artists, N.N. Rimzon is hesitant about holding forth on his work. So when I ask him to walk me through his latest show, he seems reluctant—and, as it soon becomes clear, perhaps for a good reason.

As one enters his ongoing exhibition, Forest Of The Living Divine, at Talwar Gallery in New Delhi, one is struck by the spectacular appeal of his paintings and sculptures. Warm colours dazzle the eye, towering statues seem to grow upward, and tiny figurines sprout like saplings from the floor. His style—ethereal as well as earthy, and often electrifying—blends the sublime with the sensual. The white cube of the gallery loses its impersonality and begins to resemble a vibrant rural scene, like a courtyard in some cottage in the Indian hinterland. One is content to move from work to work, seduced by the riot of colours and textures, all senses alert, and not too worried about finding meaning in the method.

It has been 23 years since Rimzon has had a solo show in the Capital, though he has been part of several group exhibitions in between, all over the world. The new body of work around us is spare but potent. On the four levels of the building that houses the gallery, paintings and sculptures have been positioned strategically from the basement to the terrace, without overcrowding them, and by keeping a certain synergy in mind. One needs to pause on each floor, soak in the energies that emanate from the various art forms, in order to be able to hear the wordless conversations they are engaged in.

“I want my sculptures to radiate an energy from the inside," says Rimzon, standing in front of a female figure, poised upon a rotund base, on the ground floor. Made of fibreglass, resin and granite dust, the sculpture is called Forest At Night, a name that conjures up multiple resonances.

When I ask him about the provenance of such mysterious figures, or the seemingly realist settings of some of his paintings, Rimzon is evasive. “All of my visual references emerge from our collective memories," he says, before admitting to allusions to paganism and fertility rituals in some of the work. For those of us who have admired Ramkinkar Baij’s sculptures in Santiniketan, in the Birbhum district of West Bengal—some of which were quite obviously influenced by the local Santhal tribes—Rimzon’s creations will ring an art-historical bell.

His paintings are strikingly simple—almost innocently figurative in their composition and draughtsmanship, until you begin to look closely at the colour palette. It is a rare gift to be able to evoke a mood of dread simply by the use of colour and Rimzon achieves this remarkably well in all his paintings.

With a patina of darkened sepia on most of them, these acrylics look as though they have been imagined through a dusky filter. As a result, the serenely rustic scenes they depict—a cottage under a starlit sky, a pond beside a hut, a dog by a shrine—reach us infused with the power of the uncanny. This continuity between the real and the surreal, mortal and divine, earth and sky, is at the heart of Rimzon’s artistic enterprise.

“Although much of my work is ostensibly figurative, my continual interest is in elevating it to another level of representation," he says, as we look together at Temple Under The Night Sky, another acrylic on canvas. With the temple at the centre, the imagery draws the eye to the brick-red sky, dotted with stars that look like fat, white droplets. The circular whorls on which the temple stands like a phallus, the stretch of inky-blue water that lies in front of it, and the trees in the background, like naked torsos, come together to evoke a primordial atmosphere, leaving behind the suggestion of something perverse hanging in the air.

The most arresting sculptures refer to the figure of the mother. Mother At The Forest, installed in the basement, is a large disk made of fibreglass that is made to look like the distended belly of a pregnant woman, with trees growing along the edges. Big Maa, installed on the rooftop, is an appositely oversized object, once again made of fibreglass, with an erect and elongated head.

While being unquestionably phallic, Big Maa is also able to retain its matronly aura with the series of breast-like lumps growing out of its slender neck. Bringing to mind some of the sculptures by the French-American artist Louise Bourgeois (especially Destruction Of The Father, which has similar bumps and knobs all over), Rimzon’s work is a classic example of a modernist sensibility interacting with several histories of thought and emotions.

Stately to behold, its imagery mysterious and absorbing, art of this kind does make one wonder about the creative process, especially about the moment when the artist is able to tell that his work is done. “The drawings I make in my notebooks, the objects I collect along the way, all come together in a thought process that is continuous with my paintings and sculptures," says Rimzon. “As for the moment when a piece is finished—well, at some point, I get the intimation of a certain truth, and then I know my work is done."

-Somak Ghoshal