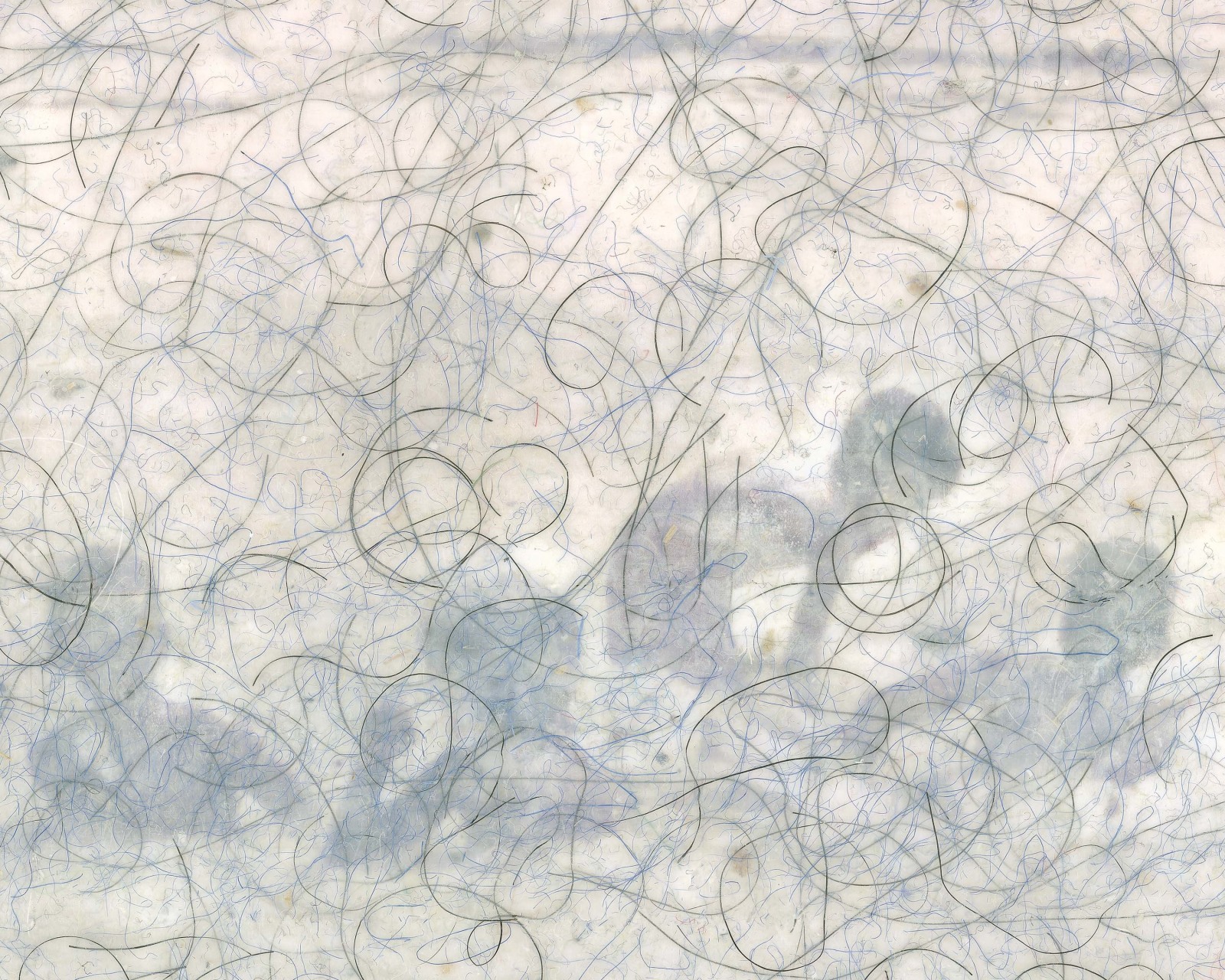

Allan deSouza's poignant exhibition explores the failings of both memory and photography as means of recording and preserving the past from aging, loss, displacement, and historical change. Based on prints of slides his father took in Kenya in 1962-3 when deSouza and his siblings were children, and which the artist left about his house to accumulate dirt and grime, the works depict snippets of typical childhood photos obscured by whirls of body hair, stains, water spots and waxy patches which resemble congealed fat or scarred skin.

In Arbor (all works 2004), the artist and his brother, in white shirts, and his two sisters, in orange dresses which match the flowers behind them, smile broadly, their images hazy through a network of stains which flattens perspective and dulls detail. In Tomorrow, deSouza and his brother stand before a billboard of a locomotive captioned 'For To-morrow', an expression of the confidence the 60s placed in progress and here a metaphor for the promise of youth that snapshots are supposed to record and to preserve. In Harambee - a word used as a Kenyan independence slogan meaning 'Let's all pull together' - a group of children appears as soapy shadows suggesting both that personal history often plays out against significant political or sociological events and that the freshness of youth and the optimism of Kenyan nationhood have spoiled.

DeSouza began this series in 2003 shortly after his mother died and shortly after a brief visit to Kenya, which the family had left in 1965 for the UK where he spent the rest of his youth. In Nairobi, he found his recollections of his childhood alien to the contemporary city. When he later described his visit to his mother, and as they reminisced, she would cut him off abruptly, saying that 'the fog was coming in, as if the process of recalling her past were overwhelming her memory. Much of what she told him about her past, proved, he learned later, to be fictitious. Immigration, illness, time, and experience had compromised and constructed her recollections as much as they had distanced the artist from his familiarity with the Nairobi of his past.

In deSouza's work, hair and dirt become metaphors for these things, collapsing the distance between the time in which the original slides were taken and in which deSouza used them, suggesting that history and memory are merely detritus of life, mediate d by experience and loss. But there is also nostalgia here: by updating the photos, deSouza attempts to merge his past and present, inscribing himself in the images by means of the slough of his daily life. By doing so, he subverts the attempt most of us make to preserve the past, and ultimately ourselves, against time and aging, insisting that life, and hence what we freeze in photographs, is physical.

-JM