An artist’s studio is perhaps what the inside of a writer’s head must look like. Materials of many kinds, paints, pencils, half-finished drawings, threads, rusting metal, and the planned disorder must resemble the words that haven’t yet arranged themselves into a sequence. Though, when I meet the sculptor Ranjani Shettar in her sometimes studio and residence in Bangalore, there is none of the chaos I had hoped to find. All her works are out for shows; her workspace-cum-home is roughly six hours from Bangalore, in a village “off the map”, near Sagara in central Karnataka. The office where we sit is huge, stark white, high ceilinged to accommodate her large installations and is now, occupied by a lone artist assistant, who brings out juice and biscuits.

To understand her work, I can now only rely on her words and images of her installations that have been exhibited across the world and have found a permanent place at the Museums of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and San Francisco, and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Delhi, and elsewhere. Like in the works at her ongoing show ‘Between the sky and earth’ at the Talwar Gallery, Delhi — all in wood — Shettar’s art practice focuses on the physicality of materials. Her works have always combined the natural, the industrial and the traditional — from beeswax, sawdust, wood, mud, cotton to latex, metal, PVC tubing, rubber to tamarind kernel powder paste and kasimi (a fermented concoction of iron rust and jaggery).

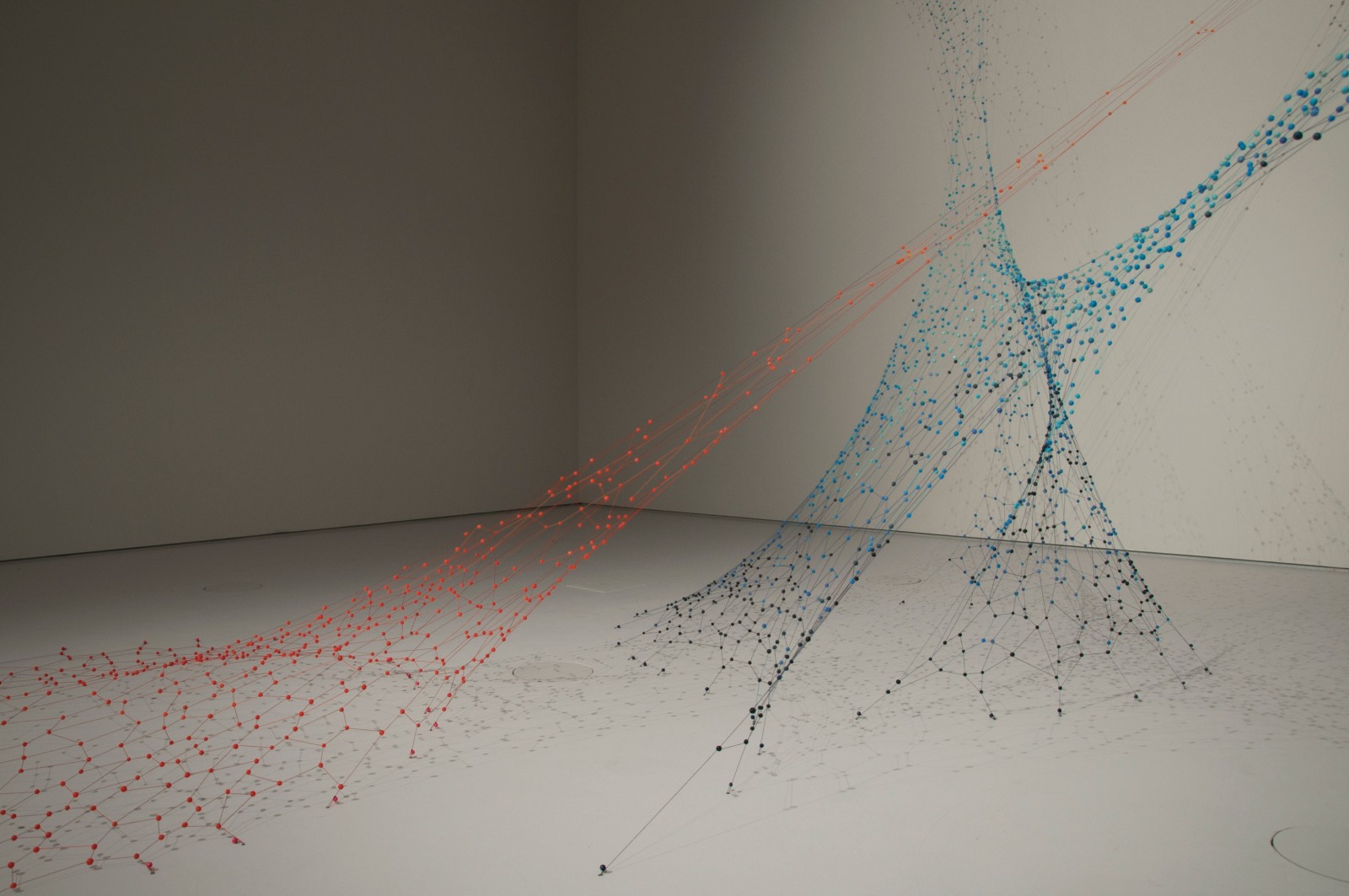

Paraphrasing Michelangelo, Shettar talks of taking away all the excess to find the form hidden inside. He referred to stone, she applies it also to other materials. When “talking to the material, I push it over a little and knock it over the edge,” she says. What culminates is a bit of an illusion where her materials seem to behave the exact opposite of their true nature, where wood floats, metal attempts to fly and threads form a strong network. This has led to her work being described by critics variously as ethereal, poised, fluid, poetic, almost whimsical, though never frivolous.

Works like ‘Fire in the belly’ follow her signature style of suspending her installations, one that harks back to her student days at the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, Bangalore from where she graduated with a Masters in Sculpture in 2000. “As a student, I used to make small sculptures that had to be displayed on a pedestal to be seen. This ended up making them look heavy. I was also playing with balance and gravity. All my imagination is three-dimensional, that’s how the installations began to be suspended,” she says.

The suspensions make her works differ every time. “'Just a bit more' has been shown four times and each time, people have told me that it looks different. The works begin to define their own physicality. When a work is suspended, you can look at it in three ways — either like it is floating, flying high or like it is falling down,” she explains. The 37-year old artist has talked elsewhere of how her works are “drawings in space”.

Her room-sized works take precise planning and detailed drawings to install, like in ‘Vasanta’, made from hundreds of beeswax pellets and dyed strings. Is the process of installing these, a work in itself, I wonder. Shettar tells me she likes to see the work as one whole unit, though it doesn’t always remain so, “The work acquires its own persona, a life of its own.” Her deliberations on space let the viewer navigate between her suspended works; the movements of people, even their breath, and the light cast from windows, all these change the way the work looks throughout the day. “I find those dynamics interesting,” says this lover of skylights.

Though the materials Shettar employs are locally sourced, her works have never been distinctively ‘Indian’ unlike the works of her contemporaries like Subodh Gupta and Bharti Kher. “I am so comfortable with my identity that I have never questioned it, never felt the need to say hey, I’m Indian, look at me,” she says, dismissing the question of identity.

We talk of titling works. They carry beguiling names like ‘Sun-sneezers blow light bubbles’ and ‘Me, no, not me, buy me, eat me, wear me, have me, me, no, not me’, names that come into being sometime over the months and years she spends on one work. There isn’t a process, though she says, “I find that when I listen to classical music, or maybe when I am reading a particular book, my verbal formulations are better.”

Shettar has been away from Sagara, working frenetically and putting up shows, for nearly a month, living the gypsy life. “When I’m not working, I feel like a different person, I feel lost,” she says. She clearly cannot wait to return to her studio.

-Deepa Bhasthi