There is an intriguing and tantalising element in Arpita Singh’s visual language. The narrative never follows a clear path from point A to point B. The artist also underscores the sense of the unknown when she talks about making the first mark on the blank surface.

“For me it is like opening a door to enter a room. I don’t know what I will find in the room. I have no idea whether it will be empty or full, but I do know that it is important for me to enter that space,” she says.

On January 29, a six-month retrospective of her works opened at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) in Delhi. Called Submergence: in the midst of here and there, the show features oils, reverse paintings, watercolours, works on paper and sketchbooks. There are more than 109 works on display.

Singh is one of the foremost modern artists of post-Independence India. She has received many awards — the Padma Bhushan, Fellowship from the Lalit Kala Akademi, Gagan-Abani Puraskar from Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, Kalidas Samman from the Madhya Pradesh Government. Beginning with her participation in a group show of The Unknowns, a body of artists of which she was a founder-member in the early 1960s, Singh has shown her works widely both in India and abroad.

Her distinctive visual language comprising razor-sharp lines, strong drawing and brushwork, a glorious feel for color and a dramatic distortion of forms, steadily developed through the last six decades, has mesmerized generations of art lovers and kept auction rooms, here and abroad, abuzz with the soaring prices of her paintings.

The note of mystery in her work is highlighted in the curatorial concept of the retrospective. “The idea of submergence struck me when I saw Arpita Singh’s paintings. There seems to be water everywhere and underneath the surface, things are happening, some of which emerge here and there, fragmenting the ground,” says KNMA director Roobina Karode, also chief curator of the show.

Almost echoing Karode’s thoughts, the citation of Singh’s Gagan-Abani Puraskar (2008) observes, “She is an artist who speaks through the acts of painting, through the whispers and silences and ambiguities of painted surfaces.”

Although it is only a select sample of her oeuvre on show, it is significant that KNMA is hosting the retrospective. Holding a large exhibition of her works is quite a major operation. Her paintings are part of collections spread all over the world. So when you count the insurance, transport costs, and the paperwork involved, you begin to appreciate the magnitude of the project.

****

So what makes Arpita Singh’s work so significant? Karode believes that Singh has “invented a language” that is very special. “It gives glimpses of stories not told, secrets not revealed. I am fascinated by her composition. One can enter it or exit from any point. Various sub-plots, sub-themes create tension. What is also very important is that Singh has remained a painterly painter. Her use of impasto [a technique where paint is placed on a surface in very thick layers] gives a remarkable quality to the surface and texture of her paintings. Much of these have come from her abstract phase in the 1970s.” Karode adds that Singh’s art practice is an ensemble of many things such as the diaries of her sketches, drawings, watercolors and paintings. Karode’s observation of Singh’s “painterly” qualities is also borne out by the cultural studies scholar Geeta Kapur, who had once written, “As for the medium of oils, she [Singh] knows better than most Indian painters how to use it to sumptuous effect.”

According to Singh, there is no eureka moment when she wakes up with the image in her mind and says to herself that this is what she is going to paint today. Instead, the idea evolves gradually. The first mark that she makes on the blank space is a scary moment for her, but she keeps thinking of what she will do and how she will do it. At that first moment of creation, how she will fill up the space is a problem, but eventually “a link is established between form, content, brushwork and color”. She experiences a moment of elation when she achieves the form that she was sensing in the subliminal terrains of her mind.

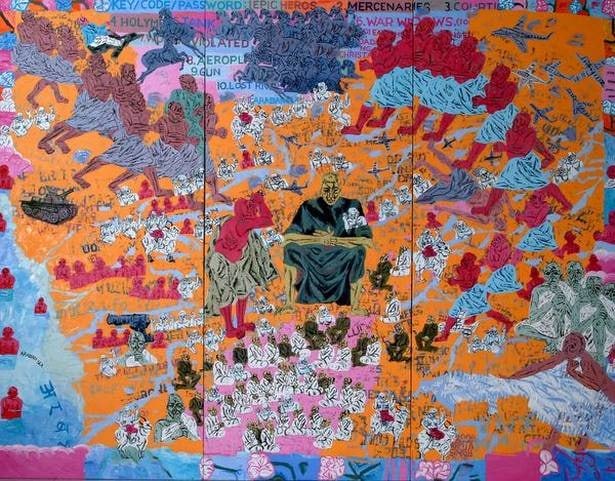

Sometimes these forms become the nucleus of another painting. In 2006, she painted a seated male figure in Man with a black jacket. She liked the man’s posture so much that she painted that very year a similarly seated male, Dhritarashtra, as the central figure in Whatever is here, a retelling of the Kurukshetra war in Mahabharata. Sometimes the form of a fruit or a flower attracts her attention so much that she creates a whole painting around it. Like the Figures around a table (1992), where a pineapple shares space with a warplane on the breakfast table around which solemn figures sit and chat, ignored by the nubile nude who faces the viewers. There are many such forms of fruits, flowers, aeroplanes, toy cars, little men with guns in their hands like toy soldiers which acquire metaphoric significance in the whole image.

For a long time, Singh has been fascinated by graphic material. Posters, billboards, printed labels, and packaging excite her imagination. Sometimes a photograph on the cover of a magazine sets her mind ticking. Like her iconic painting, My mother (1983) was sparked by a magazine’s cover photo of a massacre scene in the North-East. The space in the canvas is divided diagonally. On one side, there is chaos and disaster and in the foreground is the firm figure of her mother spelling order and calm.

Perhaps her love affair with the printed word has led her to use letters, numbers, texts as important, recurring motifs in her paintings. Singh says that the idea of using these graphic elements came to her accidentally but she finds them very useful in connecting the various elements in her paintings and establishing relationships between them. But it also gives a glimpse of her voracious appetite for reading and her ability to glean and treasure complex thoughts and ideas.

Singh combines in her sensibilities a riveting duality. On one hand, she indulges in playful fantasy, as in My lollypop city, her painting of her beloved Delhi, and on the other, she nurtures deep empathy for human tragedies. She has a clear-eyed view of female sexuality, romanticism, relationships, but she is equally sensitive towards the male figures. Above all, her works reveal an intensely experimental bent coupled with a rich, enquiring mind. The retrospective is a visual treat.

-Ella Datta