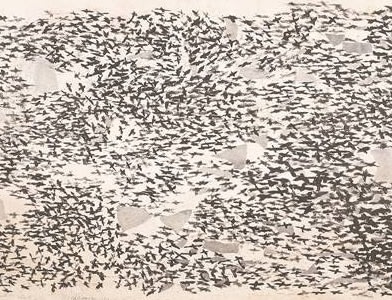

Arpita Singh describes the late ’70s as an “experimental” period in her artistic career. This is when her oeuvre took an imperative turn. Till then, painting dream-like sequences filled with motifs that referenced everyday life, Singh decided to shun colour and experiment with black and white. She replaced canvas with the more basic and accessible paper, even drawing on catalogues where the base print became part of her drawings. The depictions too altered, and the Delhi-based artist began to form shapes with lines and dots, engaging in an act of repetition.

“I felt I was facing technical problems with my work, and there were hurdles. So I decided to go back to the basics, experiment with lines and dots repeatedly; it just naturally became abstract. It was like practising handwriting. I did not want to distract myself with colour, and therefore stuck to black and white,” says Singh.

She spent almost a decade in this self-training, with an occasional urge to use colours, when small strokes of orange and yellow began to make appearances and gradually occupied more surface area in her works. It was only in the ’80s that distorted images surfaced once again, and Singh turned to the figurative. “There was a desire to put colours at times and I used them sparingly so that I remain in touch with them. The small lines in different colours appeared to be flags, and gradually as I started associating forms with recognisable things, narratives followed, and then the move back to figurative,” says Singh, 80.

Seated at her Nizammudin home in Delhi, she seems both excited and anxious about the showcase of the “experimental” works that is currently on at Talwar Gallery in New York. Titled “Tying Down Time”, the exhibition comprises more than 30 works she created between 1973 and 1982. “I thought I had lost all of them. We stayed on the ground floor and there used to be a lot of waterlogging. All these works were in boxes that had got completely wet in rain. Paramjit (husband, artist) had dried them and kept them carefully. I am very happy with the manner in which these have been displayed,” says Singh.

The previous exhibitions of her black-and-white works, she recalls, were in the late ’70s at Dhoomimal Art Gallery in Delhi and Pundole in Mumbai.Being shared publicly for the first time, the set of works in the current exhibition are in diverse mediums — ink, pencil, charcoal, watercolour, pastels and poster colours. The abstract forms too extend from bold strokes to delicate lines. There are evident references to textural patterns, possibly an outcome of her stint as textile designer at the Weaver’s Service Centre, part of the Handloom Board of India, in the ’60s.

“That time was significant and continues to affect my work even now. The broken lines do give a textured affect, for instance Kantha embroidery,” says the art graduate from Delhi Polytechnic. Describing her work at a workshop in Kasauli in Himachal Pradesh in 1975, art critic Ella Dutta had stated: “She covered the surface of the canvas with black paint and then covered the undercoat thickly with white paint. Then she scratched away the white paint revealing the black paint underneath. The markings were primitively lines and dots and the abstract markings looked like some script fallen into oblivion.”

When seen collectively, the works are not just an example of Singh’s own ability to abandon the certain for the more uncertain and challenging, but also of simpler times when commerce was no propeller for the artists. “I just kept working without thinking if the work will sell or not,” says Singh, who still continues to experiment with texture and form. Market still does not matter, not even after she became the top-selling female artist in India, when her painting Wish Dream went under the hammer for Rs 9.6 crore in 2010. Though she has continued with figurative since the ’80s, her subjects and forms have constantly evolved.

The abstract, though, is still intrinsic to her work — whether it is the repetitive strokes in the background of her compositions or the painted garments of her now-famous female figures.

-Vandana Kalra