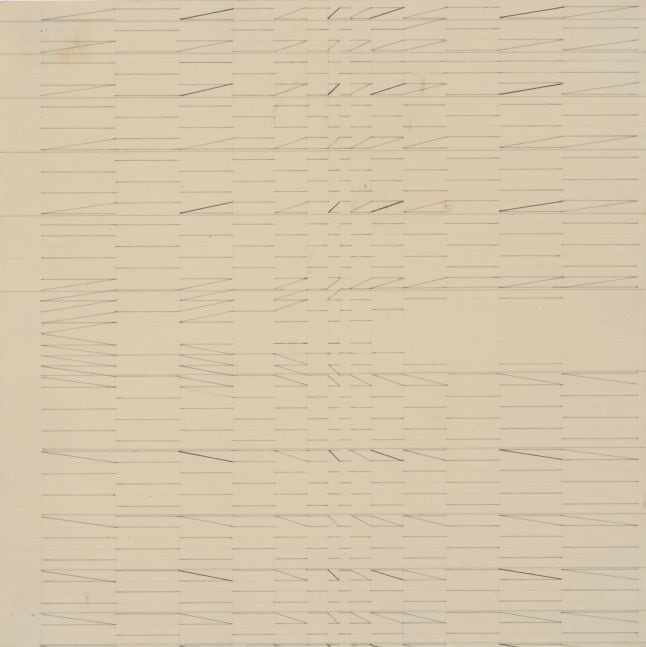

Untitled, ca. 1970s

Ink and graphite on paper

7 1/2″ x 7 1/2″

NASREEN MOHAMEDI

The Grid, Unplugged

This show of large abstract drawings is the third New York solo of work by the Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-90) and the most beautiful yet, which means it’s about as beautiful as gallery shows get.

Mohamedi grew up in a prosperous Muslim family in Karachi, then in India. She studied art in London and Paris. She spent a year in Bahrain, where her father worked. Experiencing the desert there made a lasting impression, as did the Islamic architecture she saw in Turkey, Iran and Rajasthan.

Beginning in 1972 she taught art in Vadodara, India, and produced her own work, including photographs, abstract paintings, textiles and linear ink-and-pencil drawings like those in the current show. She also kept extensive notebooks that fall somewhere between diaries and poetry journals. In the 1970s she developed Parkinson’s disease, from which she died at 53.

Word of her art has gradually spread beyond India. The Drawing Center organized a show in 2005; more work appeared in Documenta 12 last year, paired with paintings by Agnes Martin. That association makes some sense. Both artists worked with grid-based compositions of fine lines. Both created a quiet, contemplative, light-radiating art.

But there are also significant differences. Martin developed within the context of postwar American modernism. She cited Barnett Newman as an influence and called herself an Abstract Expressionist, identifying with philosophical and spiritual currents that ran through that movement. Mohamedi’s work calls on other sources entirely. A primary reference being Islamic architecture, with its purity of design and abstract ornamentation, but she also paid close attention to the Indian urban landscape.

Her work looks different, too. Unlike Martin, she departed from the grid’s vertical-horizontal coordinates with dynamic chevrons and stairlike patterns that climb up and move off into space; in band patterns threaded through with intricate networks of diagonal lines; and in free-standing forms that look like studies for futuristic architecture floating in space.

A cosmopolitan figure, she was familiar with Minimalism; she befriended Carl Andre in India in 1971; and her work is more accessible than other Indian art because Western viewers can connect her style to familiar models. Yet she is an Indian artist whose work is most accurately seen in that context, set beside that of contemporaries like V. S. Gaitonde, Jeram Patel and Zarina Hashmi. As we are gradually learning, in the realm of modern and contemporary art, no one owns turf. Similar ideas are happening in different guises all the time, everywhere.

Which returns us to the Talwar show. Mohamedi’s output of drawings was relatively small; those on view in the gallery represent a substantial sampling of what survives. The work is beautifully installed and accompanied by a digital selection of pages from the notebooks, for a moving ensemble. It is on view for just two more weeks. So go.

-Holland Cotter