Exclusive: Ranjani Shettar is the first Indian artist to have a major presentation at the Barbican Conservatory in London

Brutalist architecture and an expansive urban jungle form the context for Shettar’s thoughtful and handcrafted sculptures

By Akanksha Kamath

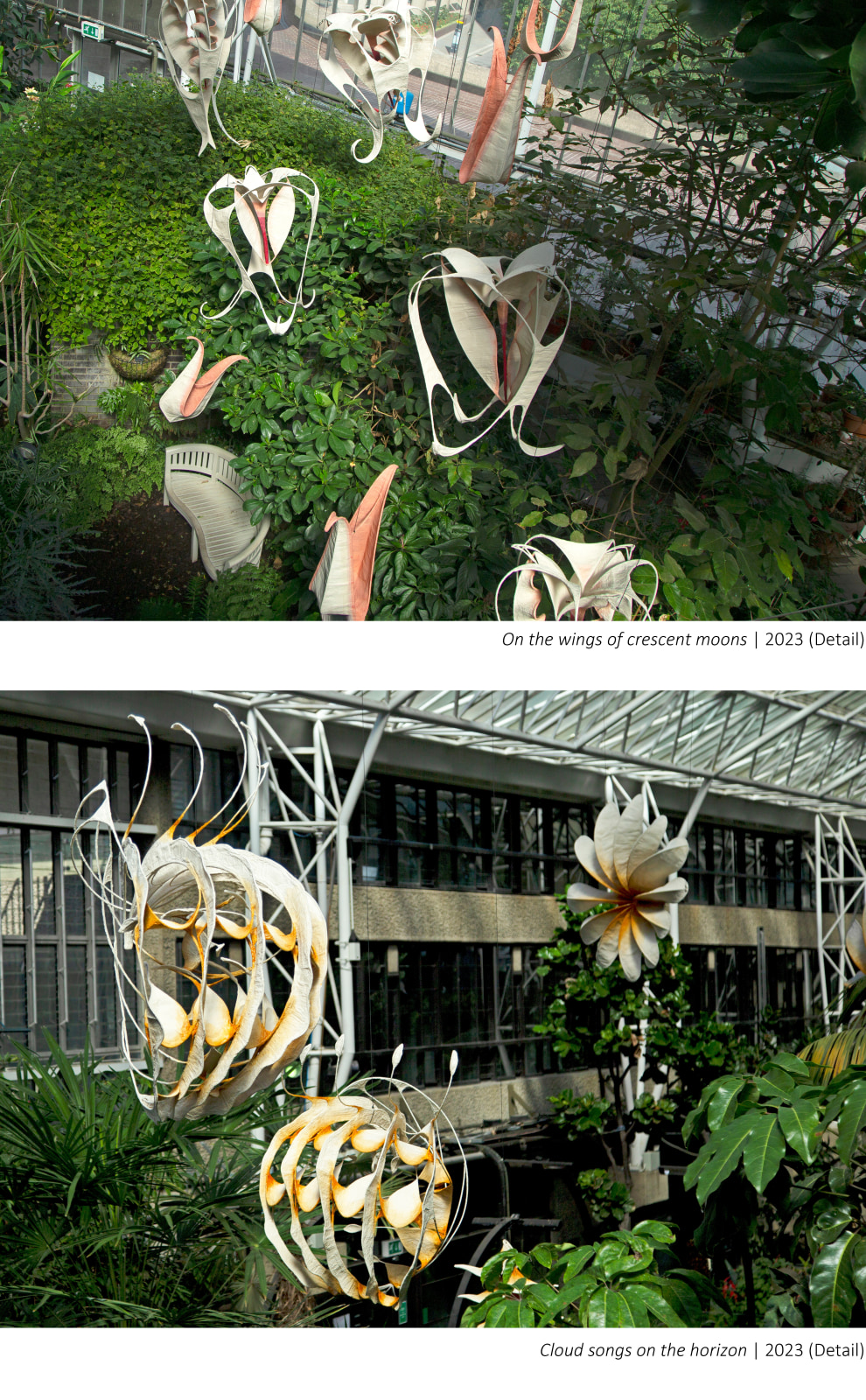

One of London’s most polarising buildings, the Barbican, built in 1982, stands large, proud and powerful in the eastern ends of the city. At its top, a 23,000sqft glasshouse provides respite to its 1.5 million annual visitors who come to enjoy everything from theatre, art, music and more. It’s this urban jungle on the topmost tiers of the building that is now home to Indian artist Ranjani Shettar’s thoughtful, handcrafted artworks. Each piece, made in her zero-waste studio in a small town called Malnad, 6 hours from its nearest city, Bengaluru, hangs quietly confident among 1,500 species of plants and trees including cymbidiums, ginger, coffee, cacti and succulents.

As you walk in, one of the five sculptures from Cloud songs on the horizon that are on display and open to the public from 10th September, greet you viscerally. Muslin dyed in madder root, wrapped around steel forms that bend, fold, foray into larger, otherworldly abstract sculptures play with light, sway in the Arid greenhouse’s ventilation and capture your imagination. Meandering through gravel paths with only foliage overhead, you won’t recognise the difference between Brugmansia (Angel’s trumpet) flower and Shettar’s artwork that mimics the colour perfectly with pomegranate dye. A stunning harmony and reciprocity is established, not knowing where nature ends and art begins.

Curator-in-charge Shanay Jhaveri, Head of Visual at The Barbican, and formerly Associate Curator of International Art at The Met, engaged with Shettar’s art in 2011. Coming together for a second time in their art journeys, he says, “Our field is also about continued relationships, seeing how practices evolve. It’s not always about going on to the next but also staying in conversation with certain people who share your sensibility and your commitment. This is quite new for both of us— I am settling into my new role at the Barbican and for Ranjani, it was an opportunity to show in a non-white space, to think about scale, in a way that she hadn’t before. In a way, we’re both debuting.”

Below, they shed light on how the commission in partnership with Kiran Nadar Museum of Art came to be and why art should help you slow down, allowing you to quite literally stop and smell the roses:

Ranjani Shettar

Akanksha Kamath (AK): 23,000sqft of space at the Barbican Conservatory—I’ve been in there before for fashion presentations and it’s a space that can be entirely reimagined with a new lens and context. How do you like to work within such large spaces? How do you see it as the perfect backdrop for your new works?

Ranjani Shettar (RS): The space is very inspiring. It’s refreshing to see an urban garden at the Barbican which is known for its brutalist architecture and concrete. There’s a surprise element. I’ve been to Barbican before, but I didn’t know about the conservatory so it was lovely to discover that and also to know how much people love that space. I live surrounded by greenery. But the urban character of the conservatory was something interesting for me. It’s also a large space. So I had to sit and think a lot about how I would handle my artwork. The simplest would’ve been to just make one large sculpture that stands out in the middle. But I really wanted to respond to what was there. Something that blends in but does not get absorbed by what’s around it. The beauty of the space is that you can see the artworks from multiple perspectives, so I used that as a jumpstart.

AK: You’re very right—we saw the artworks from the ground level and then from a mid-level on a staircase, but my favourite was when we went all the way up and got an aerial view of almost all five works. Are these all pieces that you’ve made from scratch?

RS: Two of the works were already in process. There’s always something happening in the studio. It was a beautiful coincidence that the woodwork that I was already working on could go so nicely in the space. When I came to see the Barbican nine months ago, I knew that that one piece would fit perfectly above the pond. I was also working on the piece ‘Moon dancers’, which is above another pond. That one is more linear and reacts very interestingly to the light, not just the foliage.

AK: I read that the pieces have been made in rural and remote southern India. I’d love to know where and how many hands work on these pieces, how long they take to create, and why rural Karnataka.

RS: It was about 16 years ago that my husband and I realised that we felt stuck in Bangalore, which is changing drastically. It was getting crowded and we didn’t see any urban planning in place. Culturally, you know, there was a little bit of visual art, but not like institutions and museums where you can go and spend time. We felt that we needed more space, we needed more greenery, we needed a different way of life. And that’s why we just moved. And we identified a place that is far away called Malnad which is the hilly region of Karnataka.

AK: How does where you live inform your work?

RS: We had to build a home from scratch. It’s just easier to be in touch with reality. Because we’ve done our electricity, sanitation and water supply ourselves. When we do everything ourselves, there’s a different kind of understanding about the amount of resources we are taking from the land. What are we giving back? What’s my carbon footprint for that matter? There’s a greater awareness.

AK: And that’s why you work with materials like reclaimed wood, muslin, natural madder root dye. I also noticed the forms—there is almost an otherworldly quality to it. But then it also has natural forms that mimic flowers and plants.

RS: For me, so many things become the inspiration. I’m drawn to little, mundane things. When I take inspiration from multiple things, not just one, the amalgamation of that leads to a sort of abstraction. And that’s probably what people see. I really enjoy creating these abstract poems rather than anything which is very representational.

Shanay Jhaveri

AK: Your journey in the arts is intriguing. You are deeply interested in film as a visual medium, writing as a research format, and curation is where you go from macro to micro, getting quite granular about objects and how they occupy space in culture and life. I’m intrigued to know how you see Barbican as a broad-stroke palate for contemporary art and visual storytelling.

Shanay Jhaveri (SJ): I joined the Barbican as the head of visual arts about 10 months ago and one of my first intentions was that the gallery’s programme cross the threshold of the spaces that we’ve occupied, and start engaging with the building and its architecture to meet a larger audience. The Barbican is a communal space. There are many visitors who come here. And we’re not necessarily engaging with what’s happening in the theatre or the cinema or the music halls or the cove or our gallery space. How can we continue to embrace and engage them? The Ranjani Shettar commission is the first of a series of artists’ interventions and site-specific responses.

AK: Site-specific installations are something you have favoured before with the gorgeous works of Huma Bhabha at the Met roof, which incidentally also showed simultaneously to Ranjani’s works just a floor below. What do you love about this format and what it offers sculptors in terms of a playing field and context for their works?

SJ: The Barbican is a source of inspiration to artists as well, so why not see what that dialogue looks like? The first thing that I associate with the Barbican is concrete. It has a very bulky, hulking presence. But conversely, all the concrete you see has been hand-textured. So it’s been bush hammered by human beings. There is a trace of the hand that marks the building. And so I felt that it would be interesting to bring in other practices that also have a trace of the hand. In the case of Ranjani and the Conservatory, her work has really been inspired by the close observation of nature. Immediately, I was curious to know how she’d respond to the space and what she felt about sharing the space. So her work really is more about just drawing our attention back and enhancing our experience of the space. And that’s what I really wanted. I wanted a practice that is quietly confident and can situate itself in a very large, spectacular space while still commanding a presence.

That’s also what I learned from doing projects at the Met on the roof and the facade and having the privilege of working with artists like Huma Bhabha. They kept in mind the context in which they were showing, and it was very much about embracing that rather than resisting it.

AK: When the curatorial teams and you are picking an artist to show, what are some of the parameters you keep in mind?

SJ: I think it’s about considering the context and moment in which you’re going to present a show. It’s really the artists who allow us to perceive, feel and make sense of something that feels so overwhelming. The programme has been very female-led, which we’re very proud of and want to sustain. I would like the programming to be decidedly international. We’re also very interested in supporting practices at any stage in an artist’s career. So it doesn’t have to be only emerging artists—there are so many incredible practitioners who haven’t had the opportunity and are at a later stage in their careers. It’s about keeping all of these factors in mind, and also being very curious. I encourage the team—and myself—to go out to look and do studio visits.