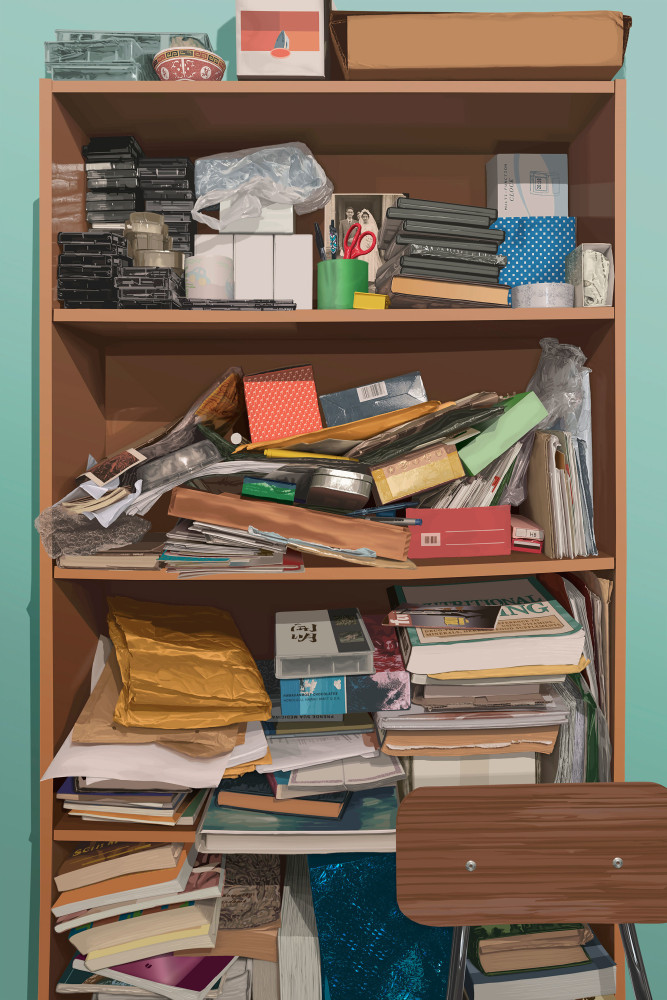

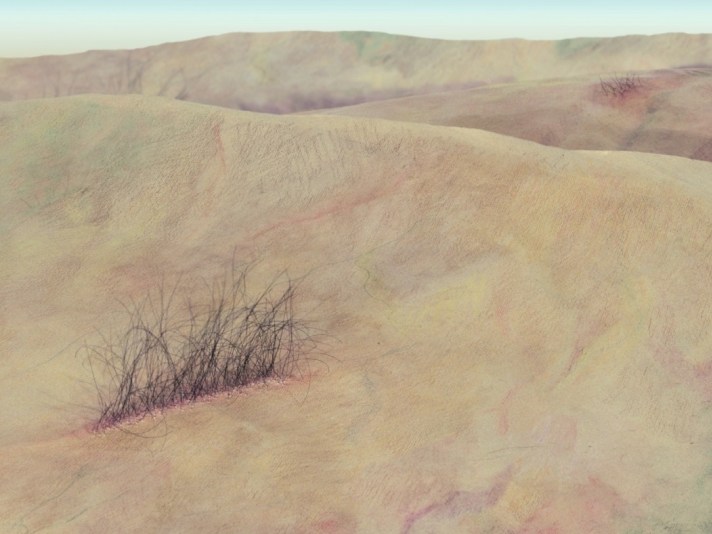

Trunk (Detail) | 2021 | Digital painting on Baryta paper | 42” x 28”

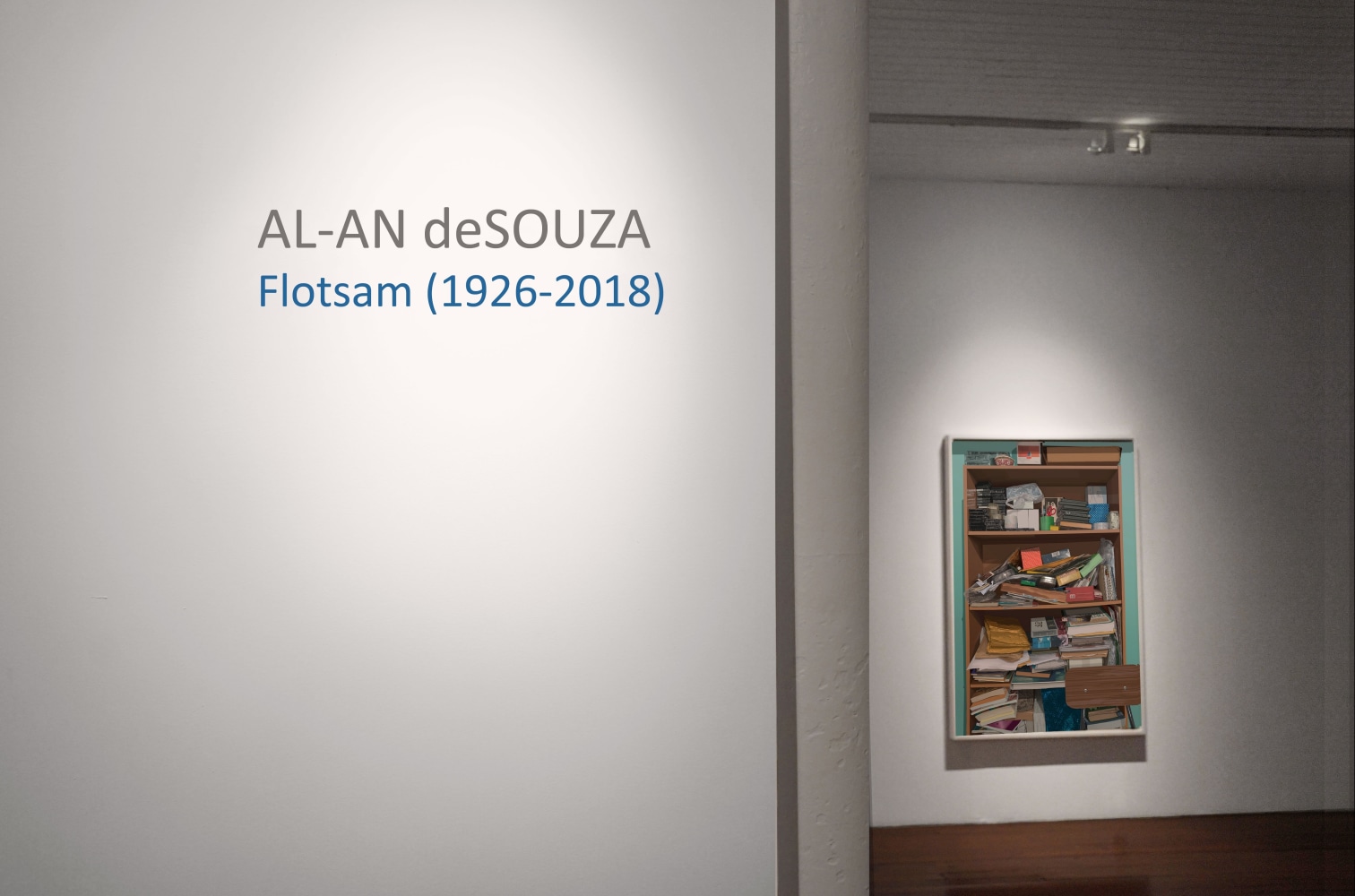

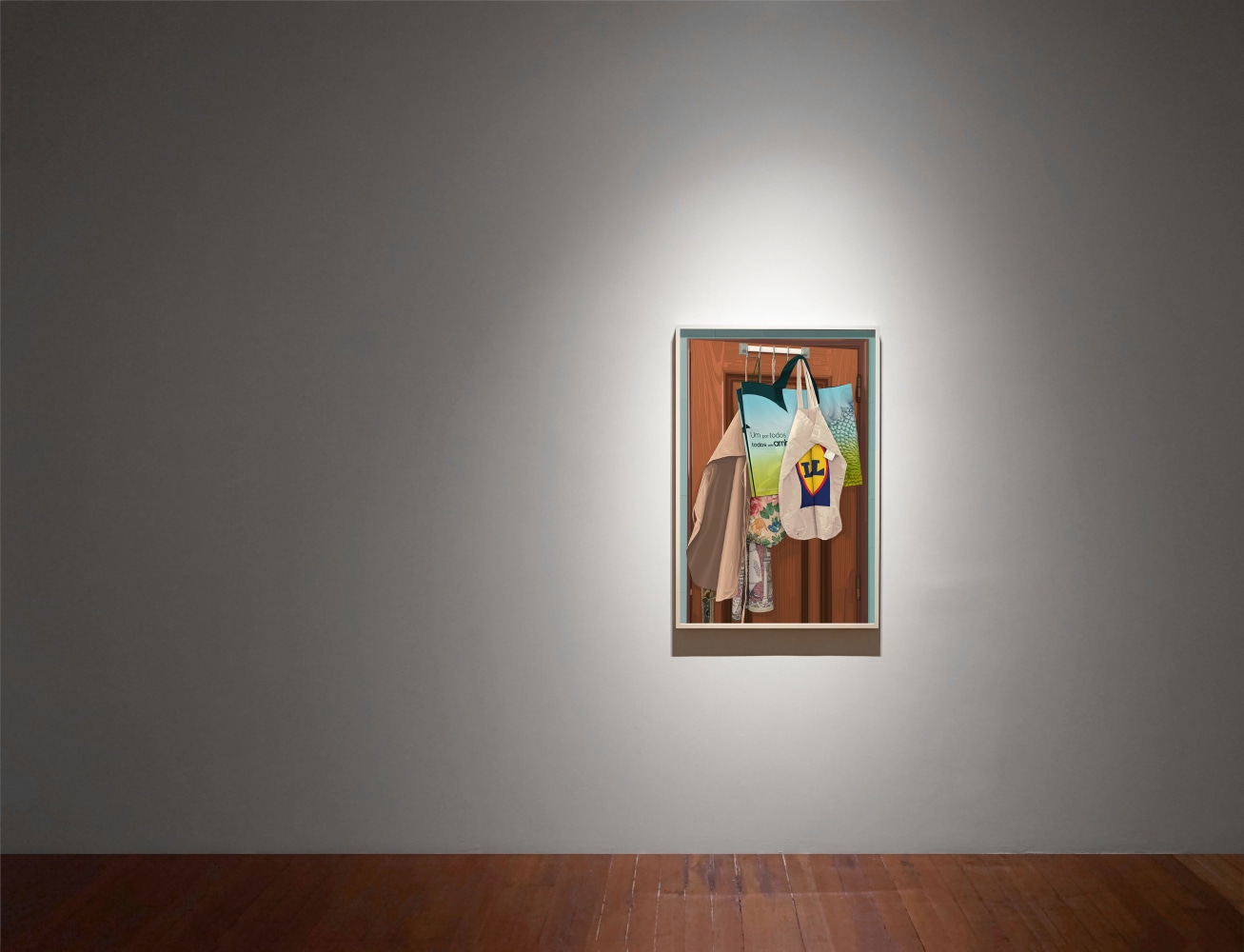

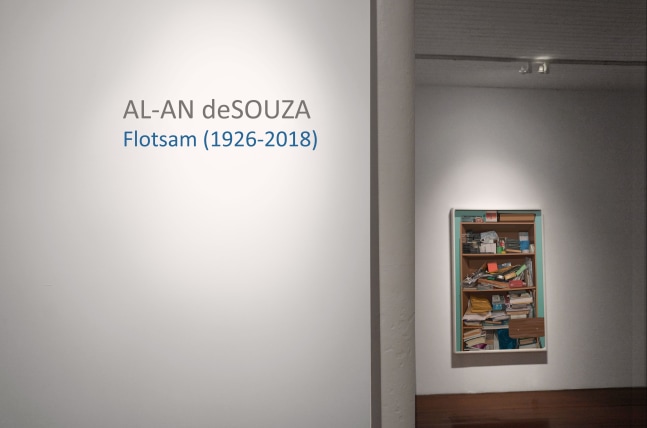

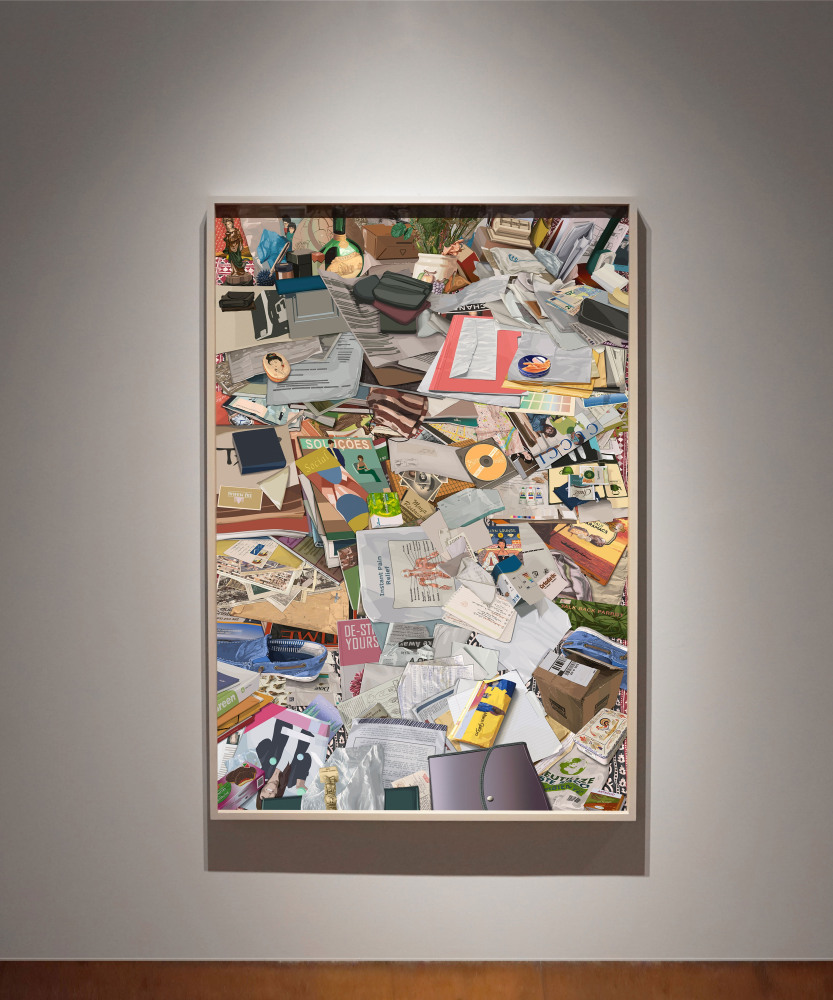

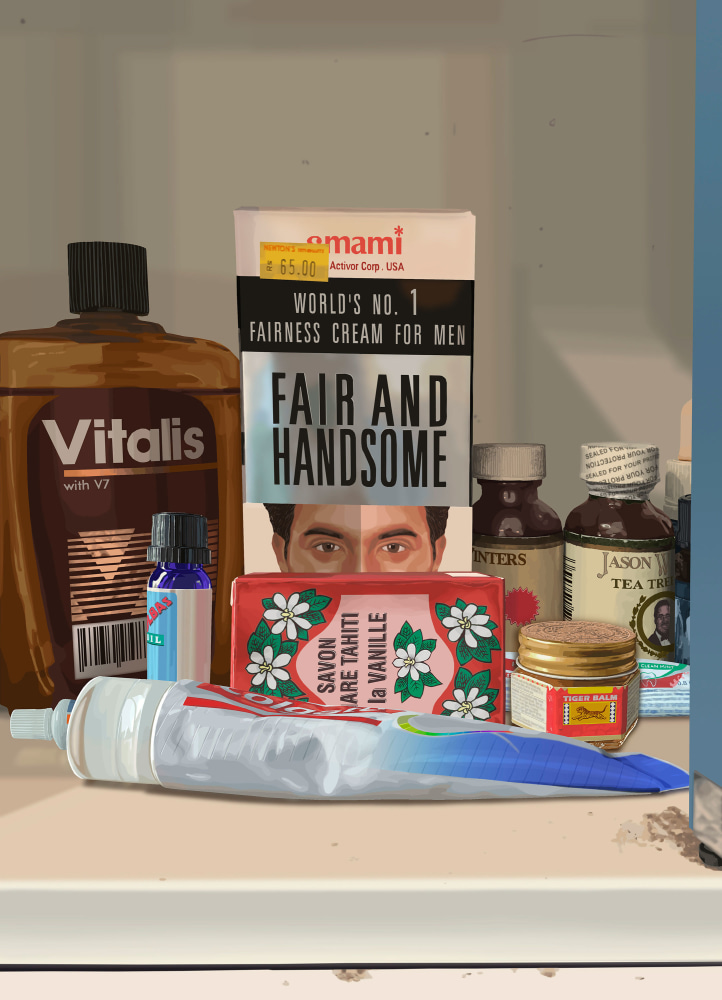

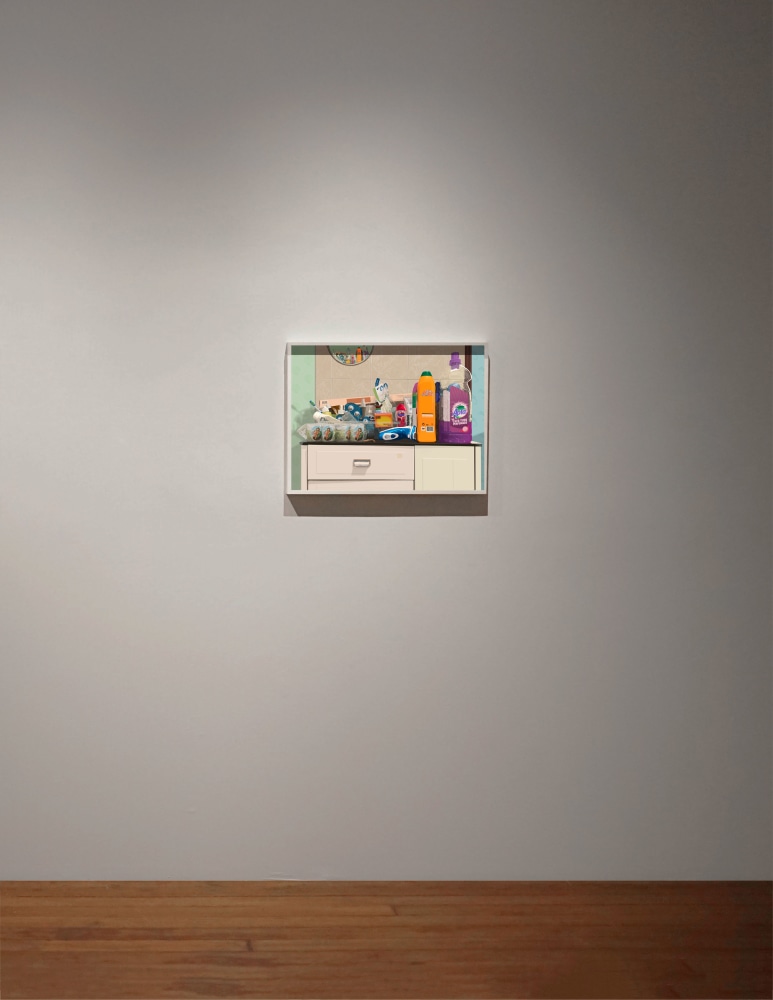

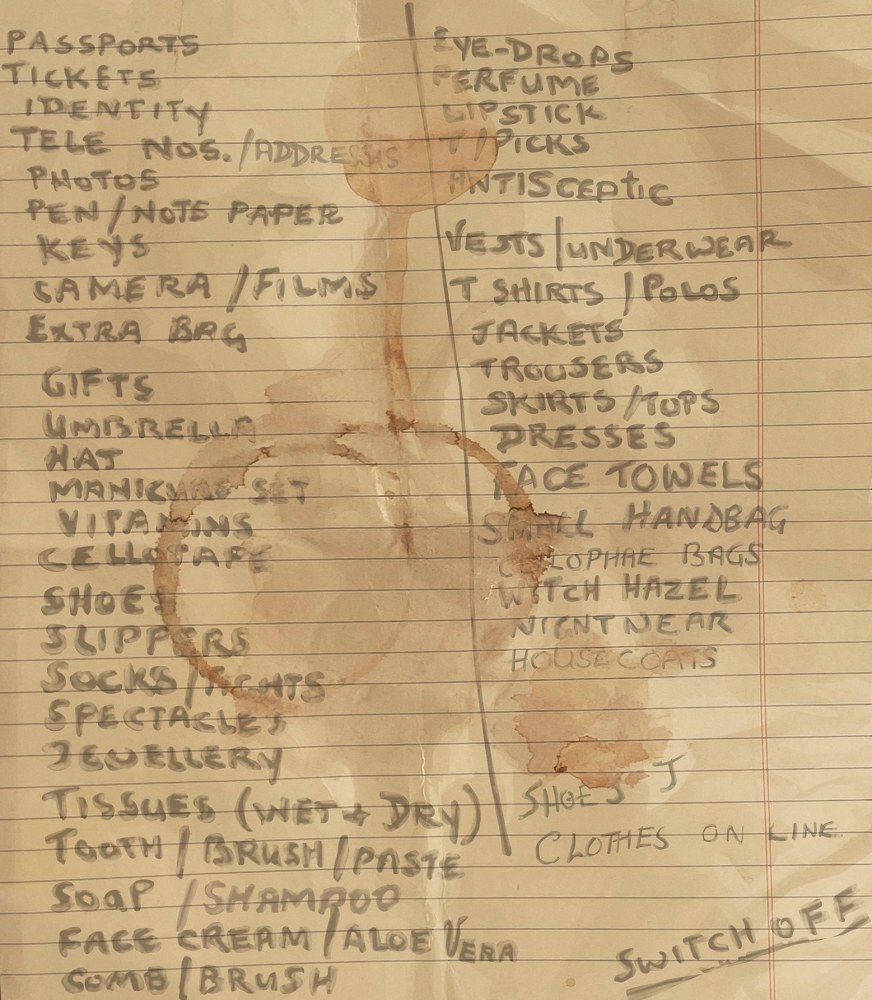

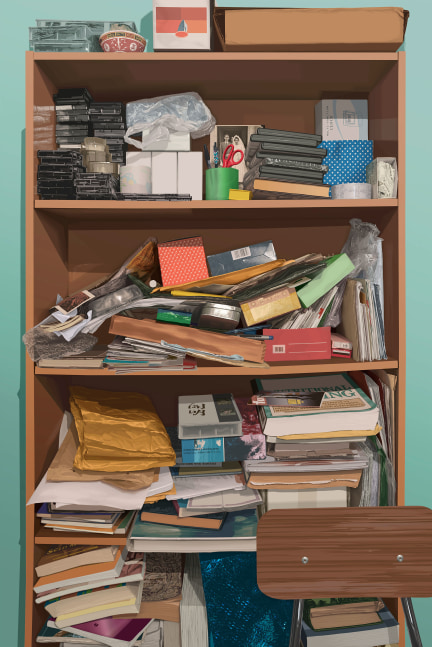

Talwar Gallery is delighted to present Flotsam (1926-2018), an exhibition of new work by Al-An deSouza. They present viewers with a surfeit of what can only be called stuff, from plastic bags to boxes of chocolate, soft stuffed toys to paper takeout menus, cassette tapes to toothpaste––the flotsam that washes up and around a single human life. Based on photographs that deSouza took of their father’s apartment after he died, the works attest to the kind of informal archive that our possessions create around us––an archive whose logic is, often, opaque to all but the person at its center. The works––which are not direct, documentary photographs but what the artist calls “renderings,” digital paintings based on a photographic original––take care to retain an element of this opacity; as one approaches them, especially, it becomes possible to see that parts have been blurred, made illegible, even erased. These methods are, in many senses, a measure of the delicacy of the revelations made in the works––a person’s possessions laid out for public viewing, as if inviting strangers into his bedroom or bathroom––as well as the personal nature of the series for deSouza, for whom creating it amounted to a form of mourning.

On first look much that seems to be junk––the “detritus of globalization,” in the artist’s formulation––the accreted materials do help to define the contours of a specific presence, a specific experience, even a specific embodiment: the shape of the body that the ghostly shirts and jackets of Trunk remember, the aches and pains referenced by various vitamins and ointments in Drift or Vitals.

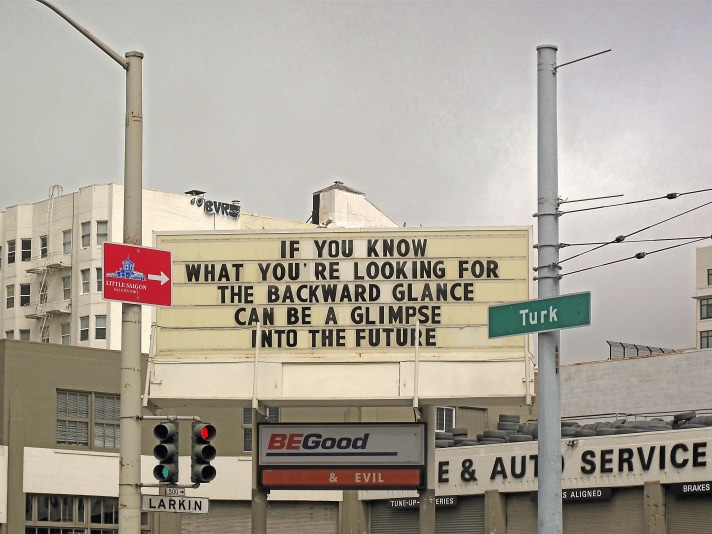

"My photographs have always addressed the issue of temporality, and have resisted the idea of a photograph being a single fixed moment."

Al-An DeSouza

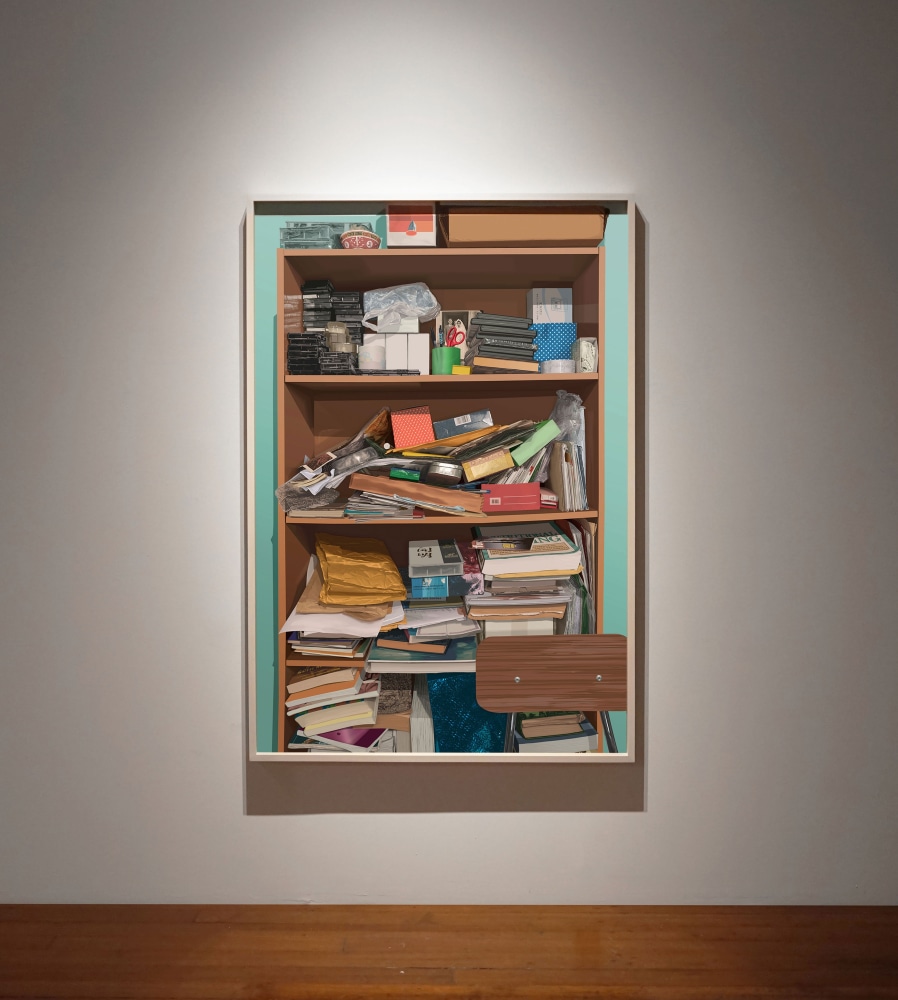

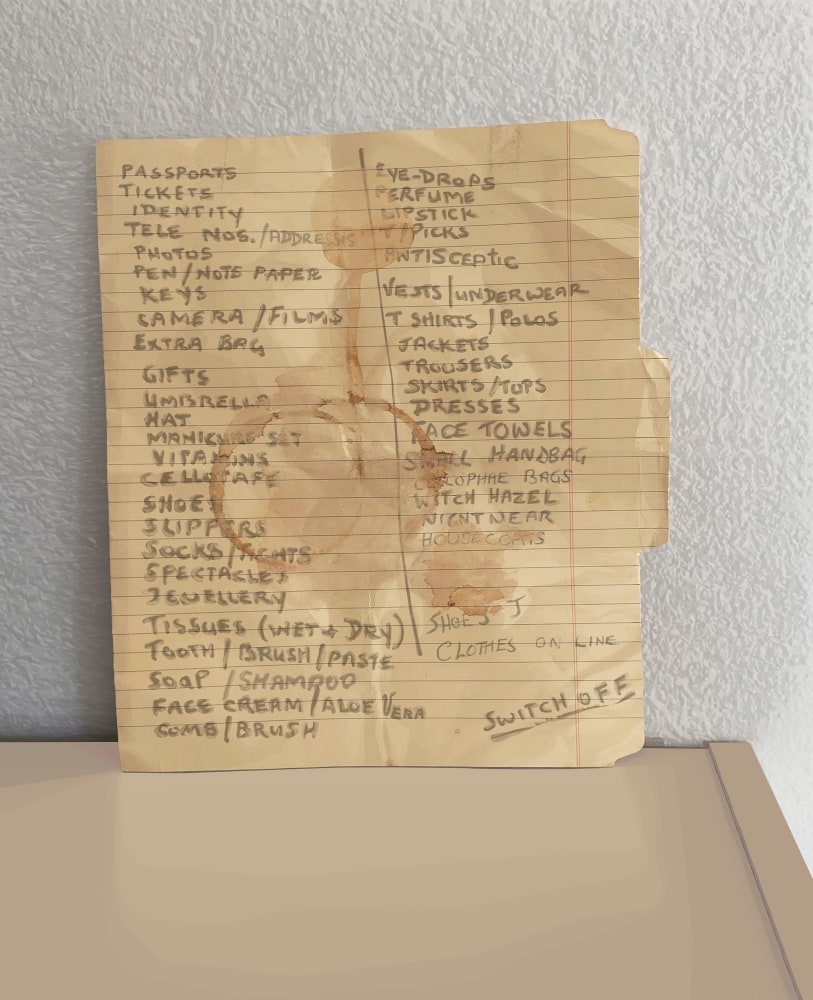

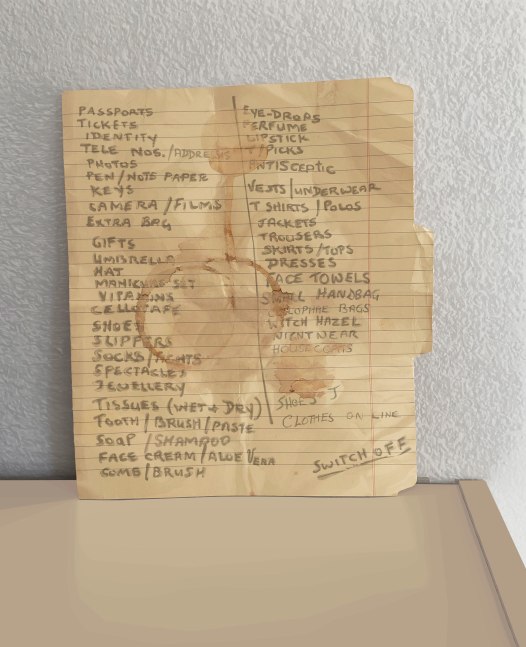

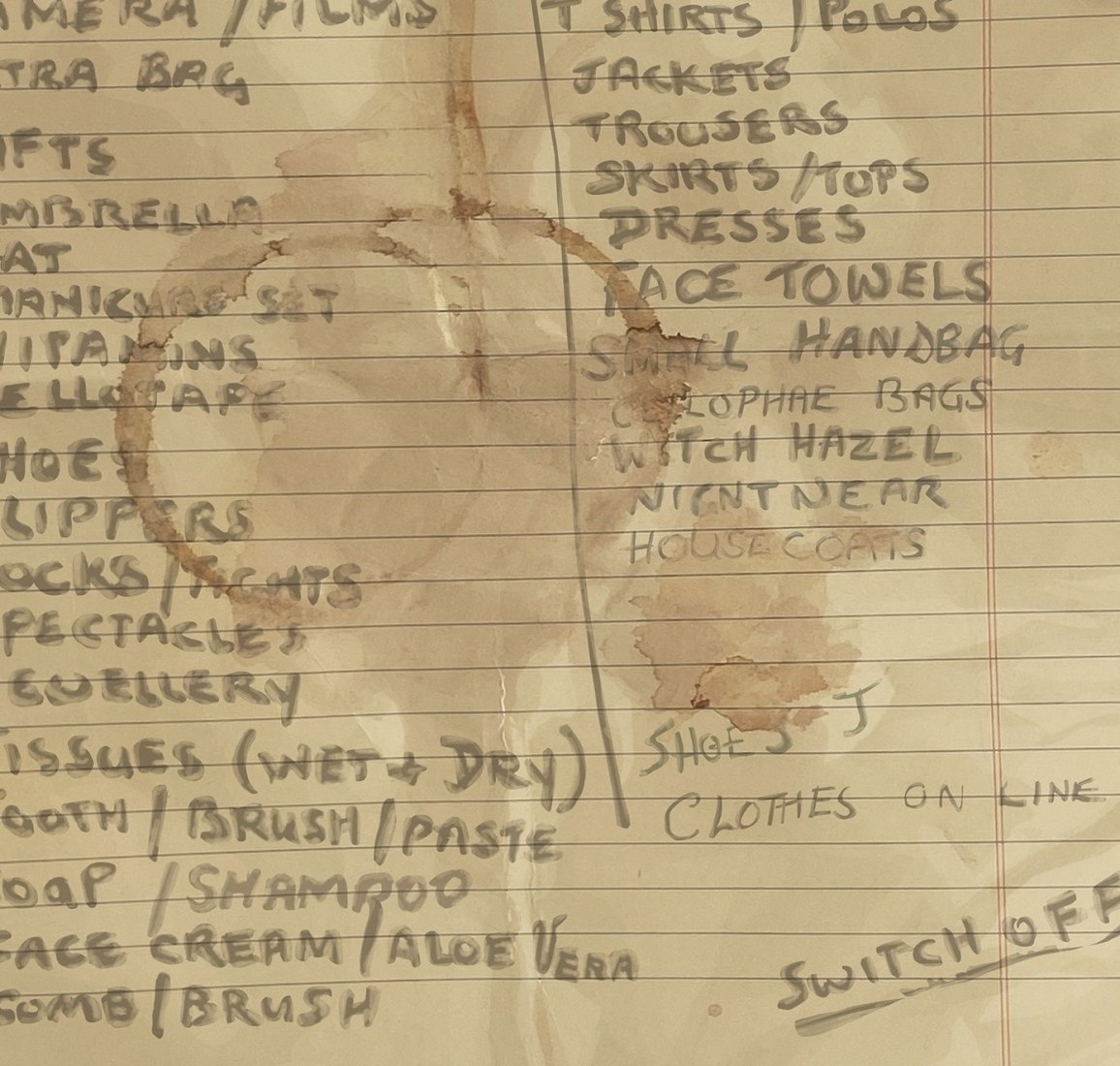

Switch (Detail) | 2021 | Digital painting on Baryta paper | 16" x 13"

There is even––in the mix of languages glimpsed on labels and bags, in the postcards mingled among magazines and books, in the well-worn packing list that appears in Switch––a sense of a life lived in constant motion, of intimacies carried out across the scattering of a diaspora––a sense only underscored by the gestures at seaward journeys made in the works’ titles (Portal, Dock). If this is a kind of portrait, though, it is one glimpsed only in fragments, never as a single, coherent whole; mirrors, where they appear, are always blank, or else winkingly withholding. These works force us to look otherwise, in other words, not swiftly or singly but painstakingly, pondering adjacencies and shuffling through redundancies—gleaning what we can, fleetingly, from the flotsam within them.

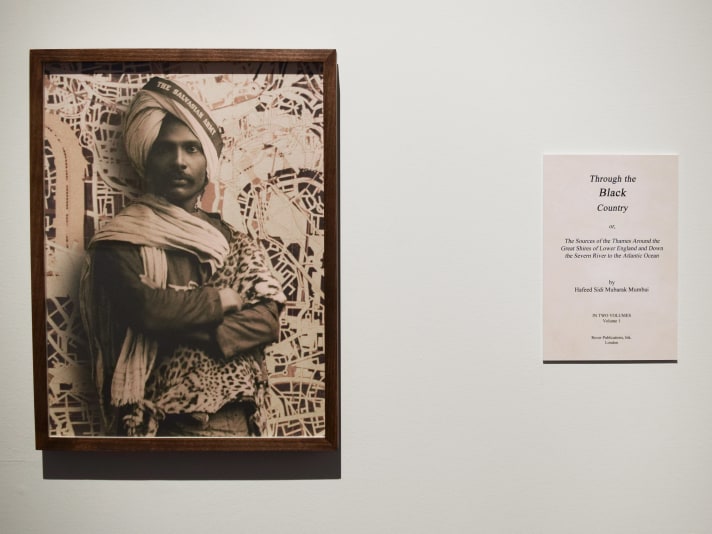

Among the piles and stacks of materials in Flotsam, there occasionally appear photographs — a set of black-and-white portraits, spilling out of an envelope in Album, or a wedding photograph of a young couple, whose serious faces peek out from the piles of boxes and papers in Stack. These are family photographs, mostly images of deSouza’s parents in their younger years, which the artist chose not to paint or alter in any way—heightening the contrast between graphic and photographic within each work, while also sharpening the piercing specificity of the photographic index.

"deSouza directs us towards the malady of modern existence: exile, diaspora, dislocation.”

OKWUI ENWEZOR

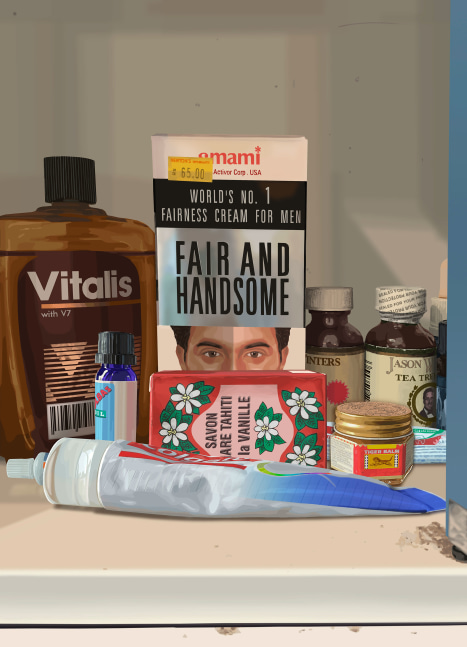

Blossom (Detail) | 2004 | C Print | 40" x 60" (from The Lost Pictures series)

The decision also puts Flotsam in conversation with deSouza’s earlier series, The Lost Pictures, which they made following their mother’s death—although in The Lost Pictures, the photographic substrate was gradually broken down rather than preserved, as the dust and detritus of everyday living gradually obscured the childhood family photos while the artist painstakingly marked over their mother’s portraits, each mark sculpting a tribute.

The continuity between the two series speaks not only to the artist’s sustained attention to the way relationships are strained and sustained across distance and time—but also to their consistent probing of the possibilities and limitations of the photographic medium. deSouza brings a similar sensitivity to each media, genre, and process that they use––from fiction to film, photography to painting––working across the gaps between them even while manipulating the conventions associated with each. Deploying a subtle, if often flaying wit, as well as a masterful knowledge of art’s histories, deSouza’s works ask viewers to become similarly aware of their own habits of looking, and the many ways these habits are mediated, circuited, reinforced, normalized –– thought, or allowed to go unthought.

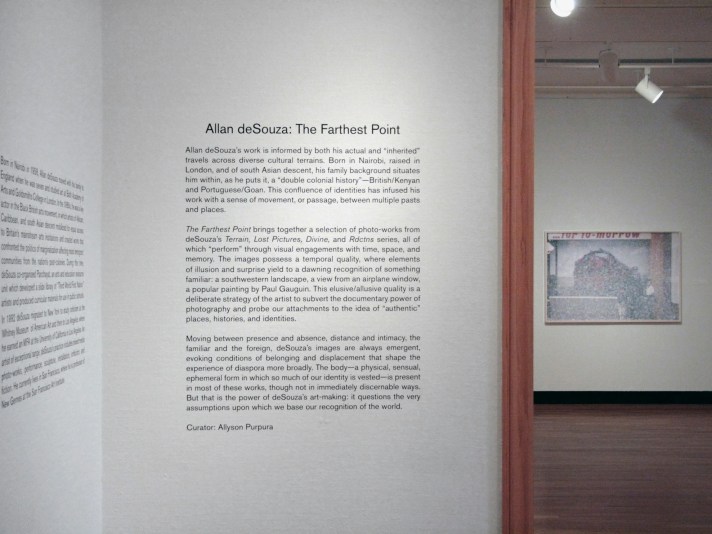

Al-An deSouza in Dreamlands | Centre Pompidou

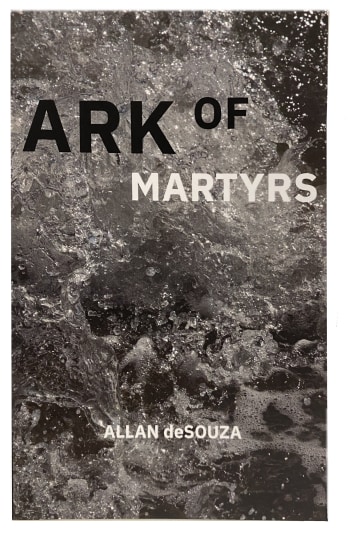

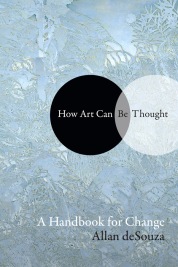

Born in Kenya to parents who migrated from India, deSouza grew up in the UK, where they were involved with Britain’s Black Art Movement in the 1980s. Since 1995, deSouza has been working and living in California with the past decade in the Bay area where they are the Chair and Professor of Art Practice at University of California, Berkeley. deSouza’s works have been exhibited worldwide including at The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Krannert Art Museum, Champaign, IL; International Center of Photography, NY; Museum for African Art, NY; Smithsonian Museum of African Art, DC; Philadelphia Museum of Art; 7th Gwangju Biennale, Korea; 3rd Guangzhou Triennale, China and Fowler Museum, LA. deSouza has also authored numerous articles and their recent publications include How Art Can be Thought in which they examine how art is discussed, valued and taught within a politicized global culture while in their novel Ark of Martyrs the artist pens a fictional rewrite of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel Heart of Darkness blending poetry, rap and prose through a contemporary prism.